Bombs dropped in the borough of: Lewisham

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Lewisham:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 1,128

- Parachute Mine

- 20

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Lewisham

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by nationalservice (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was added to the site by Justine Warwick on behalf of Alan Tizzard. The author is fully aware of the terms and conditions of the site and has granted his permission ofr it to be included.

This is the story of how wartime stole my childhood and forced me to become a man

Saturday the 7th September1940 was a glorious summer day. I was 10-years-old, sitting in the garden of my parents home in Hither Green Lane just off Brownhill Road, caught up in the knock-on effect of the teacher shortage at Catford Central School in Brownhill Road and attended mornings one week and afternoons the next.

This was the case for those of us whose parents would not be parted from their children, or whose wisdom suggested something was fundamentally wrong with evacuation to destinations in Kent or Sussex. Surely these places were nearer the enemy across the Channel?

Anyway, I was at home with my mum, dad and older brothers and sisters and it was great!

My dad, because, he was a Lighterman and Waterman on the Thames and had been a policeman, found himself on the fireboats patrolling the river to

put out fires caused by enemy planes. My brother-in-law Jim was in the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) stationed in a nearby school. He drove a commandeered London taxicab that towed a fire pump trailer. Brother Ted was a peacetime Royal Marine, serving on HMS Birmingham. Brother Chris, at 16 years was crazy on American gangster films and used to make wooden models of tommy guns they used. He encouraged me to make model aircraft from the Frog Model kits of those days.

On that sunny Saturday afternoon in early September I was sitting on the kitchen step whittling away at my model when the sirens sounded. No sooner had the sirens stopped than the fírst planes came into sight. They were high, by the standards of the day, maybe twenty thousand feet. Hurricanes and ME109's. They were twisting and turning, weaving and bobbing. To me this was a grand show. So far my sight of war had been at a distance and knocked the cinema version into a cocked hat.

Suddenly what had been a spectator sport, not wholly real changed to War. I was to leave childhood behind forever.

From the front of the house we did not see the approach of that part of Luftflotte Zwei from across the Channel as they came from behind us. A sudden shower of spent machine cartridge cases rained down all around us. What had been the relatively dull ever-changing drone of the fighters in dog-fights high above our heads with their guns making no more than a phut, phut changed to pandemonium. The stakes had changed. We were now a part of it.

Chris said: "I think they're trying for the bridge." As he spoke, a Heinkel 111 flashed into sight coming in at an angle from our right. I believe it was being chased by a fighter as another shower of empty cases came down, bouncing and pinging on the front garden paths and pavements. Suddenly an aerial torpedo fell away from the Heinkel, which seemed to bounce higher into the air as the weight of the missile fell clear. The Heinkel disappeared, climbing away to its right out of our sight. Some seconds later we heard the explosion.

Two.

Later, in a conversation, my brother-in-law t the AFS man stated the showrooms had copped it from an aerial torpedo. From his comments and the first hand observation of my brother and myself that afternoon, I believe the Heinkel 111 we saw was the culprit.

I am not sure. But this much I know that was the day I stopped being a little

boy. I think it was seeing German planes still managing to fly in formation not withstanding all that the Hurricanes were doing to try to stop them, that took away my innocence.

Two days later, on the afternoon of Monday September 9,I answered a knock at the front door of my parents' home and was taken aback by the spectacle of a man so covered in oil and filth from head to foot that I didn't at first recognise my brother-in-law. Jim the firefighter had gone on his shift on the afternoon of 7th and had only then returned. Calming my alarm at his state, Jim explained that his unit had been in I he docks fighting fires

for over 72 hours and that at one point had been blown into the oil-covered waters.

The filth laden atmosphere pervaded the air for days. The sky to a great height wreathed with smoke of all colours that glowed red, orange and in some places blue.

Soot seemed to fall contínually and as you wiped it away it smeared your hanky and smelt of oil.

On the afternoon of the 11th September the sirens went again. We were all getting very weary from the raids, Í was little more than a young child and I had, had enough. I can't imagine what it must have been like for the grown up members of my family. ^^^H

Certainly, we had by now we had given up trying to brave it out when the bombing got local. So my mother, two sisters, my brothers Chris and Arthur and Jim, all climbed into the Anderson shelter in the garden.

Usually the doors were pretty firm. But things were really getting hot outside. All hell was going on out there

The door was hammering against the shelter and coming loose - at one point Jim leapt forward and simply held on while I was pushed to the floor and my sister Maisie threw herself on top of me As I lay pinned down I could see Jim rocking to and fro at each blast from outside.

I don't know when, but in due course things became quieter, and Jim climbed out. I don't recall actually leaving the Anderson, but I do

remember what 1 found outside. My mother's orderly wartime garden, her pride and joy, was a wreck. The back door to the house 'was laying in the yard. All the rear windows were gone, where the frames had survived shreds of what had been net curtains hung in tatters.

The whole house was in tatters. The road outside was a shambles, everywhere were those empty cartridge cases. Arthur and I started collecting them looking to see if they were theirs, or ours. Over on the other side of the road, a showroom was burning, soldiers were milling around some kind of control vehicle with a dome on top painted in a chequer-pattern. I believe they must have been bomb disposal chaps.

Three.

I remember later, in the back garden my brother Arthur endeavours to chop with a garden spade the burnt half of an otherwise un-burnt incendiary bomb that he had found in the front garden.

The whole thing had an unreal feeling about it. It was then that my family moved.

I have no recollection of any decision being taken by my elders to leave the house. I do recall being in the back of what must have been a 15-cwt Army lorry with some but not all of my family. The vehicle bumped away from our house and as I looked through the back I was being cuddled by my older sister Maisie. The sky was yellowy and smoky. Opposite and to the left of our house five houses had five houses had their upper floors torn away, our lovely Methodist Church and my cub scouts' hall had totally disappeared.

The 15-cwt turned left into Wellmeadow Road and made its way to the rest-centre at Torridon Road School where we remained until the 15th September before temporary evacuation to Sutton-in-Ashfield Notts. We returned to Bomb the Alley of southeast England after a short respite and I regarded myself as grown-up for the remainder of the war.

NB:This article written by me appeared in The Greenwich Mercury November 28th1996.

The article was accompanied by two photographs one of me in my parents wartime garden of the house from which we were bombed out shortly after it was taken.

The other photograph was taken in 1954 following my return to England having been in the Occupation Army in Germany.

The little girl in one of the pictures was Joyce Eva Maycock of Hampton Village, Evesham, Worcestershire a sweet little thing from the country not realising she would later marry the urchin above. (as I write this Tuesday, August 03, 2004 come tomorrow Wednesday 4th August 2004 we shall have been married fifty years)

Contributed originally by Charles Nightingale (BBC WW2 People's War)

I was only one at the outbreak of war, one of four children born between 1935 and 1941. Memory starts with seeing my brother brought home after he was born in 1941, when I was just three. We lived in the road that led from Penge to Crystal Palace. At least four houses in it were flattened, and more than half including ours were damaged. I do not recall the collapse of our roof but was often told of my fathers dramatic trip up the stairs through a fog of powdered plaster, to rescue me: I was 'miraculously' lying in my cot surrounded by debris, yet unharmed. My mother has told me that one night at the height of the night-time blitz, she and my father abandoned hope, when the bombs seemed to be setting fire to the whole neighbourhood. They lay in each others arms waiting for the end with the sound of Armageddon in their ears. The sky, all around, was flickering red she said.

Mostly, though, we used to sit under the stairs wearing ghoulish Mickey Mouse gas-masks. My mother had Edward, my youngest brother inside a sort of capsule into which she used to pump air, whilst my father was fire watching. There were frequent air-raids which I enjoyed, because I was brought down stairs. I felt no fear, I didn't think we could be hit, since my mother showed no fear herself. I knew that people were hit though. At a nursery school I attended one child stopped appearing at school and I heard that she had been killed. I recall her name, Valerie, because I had sat next to her for a time. I kept her drawing book in which she had painted what she said was “A pea family”. I guess she had been told the flowers she drew were members of that botanical order.

During the raids my mother used to look into a coal fire which we could see from the door of the “air raid shelter”, and make up stories which were inspired by shapes she showed us in the fire. After the war, I boasted about her apparent courage when my first 'girl' came to tea. My mother interrupted: “I was in a state of blue funk from start to finish” she said. My father was not afraid though - he had been in the trenches and fought in the Battle of the Somme. He had got used to being shelled all day every day. “But as long as you don't have to do anything” he said, “its OK”. Neither he nor we thought anything of his Somme medal. “We all got them” he told us – no heroics then – we believed him.

Each morning after a raid we ran to school, hoping to see new bomb damage, and find shrapnel which boys collected. We backed onto the cricket field in the Crystal Palace Grounds (now a park, then being used by the army). One could trace the line of bomb craters, like a malevolent giant's footsteps stalking across the field culminating in a direct hit on a large nursing home (Parklands). This was largely destroyed leaving only a beautiful dome almost like the Hiroshima memorial. Like all the kids we played amongst the willow herb in the dangerous ruins. We and our friends 'owned' bomb-craters which remained for years after the end of the war. The water filled ones were very educational - with dragonflies, water-boatmen, water-spiders and so on. One night an incendiary bomb fell in our tiny front garden, and my mother couldn't open the sack of sand you were supposed to empty on them. She says she tipped the cat's earth box on it - but I have no recollection of that. Another time the soldiers in the requisitioned house next door, who we children had befriended, pulled us into their practice trenches when a siren suddenly sounded in the day. I looked up and saw a plane screaming across the sky with tiny sparks on the leading edge of its wings. For us it was a Spitfire shooting down a Messerschmitt, but of course it might have been the other way round.

When the V1's began to arrive it was very terrifying, as they sometimes came with no siren. When their engine cut out, the residents below had a few uneasy seconds to wonder where they were going to land. It was said you could hear them coming through the air, if they had your house number on them. We were fortunate to survive a narrow escape, but it pushed my poor mother into a nervous breakdown. She had set out with us from Crystal Palace, to visit Horniman’s museum which was situated in nearby Forest Hill. As we came out of the house, I looked up and saw what appeared to me to be an odd-looking aircraft. I was familiar with the shapes of the more common planes that flew around, but this seemed quite unlike them, having very stubby wings. Whether this was the V1 that occurs later in the story I don't know. If it was, it must have circled around for at least fifteen minutes before it fulfilled its purpose. We took a bus near to the museum - and stopped off at a sweet shop. There my mother got into an argument with the shop assistant who was talking with another person instead of attending to her. We were all obliged to walk out as an ostentatious demonstration of my mother’s anger. We children were not pleased as we walked along toward the museum. A few minutes later there was the loudest bang I had ever heard, and some of us fell down. As we got up we saw that a bus had stopped at a rather acute angle to the kerb - I don't know if it was pushed there by the residual blast or if the driver reacted in surprise. He looked at us and asked us if we were hurt. My mother was very shocked, and he offered us a free ride back to our street which we accepted. As we went past the row of shops my mother shouted that the sweet shop, from which we had walked in a huff, had been 'bombed out'. I looked and saw a lot of bricks and glass lying at the side of the road and people running out of surrounding buildings. Later on she used to swear that the shop had been completely demolished, but I don't recall seeing any actual gap in the stand of shops.

Shortly after that my mother told my father that she couldn't take any more and we left for Oxford to stay with relations. My mother just wrote them a letter and set out once she thought they had got it. On the way we saw the build up of war materiel at the side of the track. I watched a Bristol Beaufighter land amid huge clouds of smoke. My mother asked my father if it had crashed, but I think it was just dust on a hot summers day. All the aeroplanes and gliders had black and white stripes on their wings - all boys knew them to be 'invasion planes'. On the train a kind older couple agreed to take my two older sisters for the night. They later reported that they were terrified and thought the kindly woman was trying to poison them when she offered sweets. On arrival at Oxford I got lost, and was taken in hand by a WAAF who sat with me where she found me, until my father reappeared. As we approached the house of my aunt we saw her sitting in an upstairs window. I couldn’t follow the conversation between her and my mother, but in later years I heard that it went something like this. Mother – desperately: “Did you get my letter? Aunt - frigidly: “yes – but didn’t you get my telegram?” We stayed in Oxford for 14 weeks with a nice old couple who couldn’t have been kinder, with five extra people to cope with – my father having returned to London. We took a trip down the river to Abingdon, our steamer staying close to another one full of young men in cobalt blue uniforms, some with manifest injuries. “Aren’t they quiet?” my mother said to two ladies we were befriended by. It turned out they were convalescent American aircrew. “They are on our side” my mother said. I have never forgotten their white uncertain faces. They had seen the horrific face of war.

The V1 menace passed as the invading forces overran the launch sites, and we returned. On the way up the hill from the station we heard – out of the blue – a sudden huge bang. It was the second loudest I ever heard, after the V1 in Forest Hill. We got home very shaken, to hear later that a new weapon had been launched at us – the first of the V2 rockets. Even aged six I could see how crestfallen my poor mother looked. And a week or so later her sister’s flat was badly damaged when one hit one end of Park Court, the stylish apartment block lower down the street in which she lived with her son. The boy, who was my age, told me he had looked at the wreckage and seen the V2’s nose “with German writing on it”. At the time I believed him but of course it was nonsense. His mother broke down and my elder sister later acted out the sudden collapse in tears which she had witnessed. “Uncle Jim hasn’t written since he was taken prisoner”, she told us. He had been captured at some point, which my mother rather callously told us “was not very glorious”. Other husbands, sons and fathers were not so lucky. I recall a discussion between my sympathetic mother and a friend who had lost a son, where the phrase “right through his helmet” in a rising tone of distress culminated in a hysterical outburst which I found frightening.

I was in bed when news of the surrender came. All the electric trains whose tracks infested the area stopped and turned on their strange whistles. The next morning the world was exactly the same, but completely different. It was a sunny day and looking at the urban flower beds near the shops I got a picture of blue sky, green grass and scarlet flowers, and it was peace. There were lots of celebrations, and we walked up to Crystal Palace and looked out over the city where bonfire after bonfire into the distance were blazing like ever receding sparks.

The park with its bomb-craters and its reel upon reel of barbed wire and other seemingly unused equipment was cleared by the German prisoners and we befriended them as we had the soldiers before them. One said to my mother “We give you tea, we demand coffee”, just like a real German was supposed to talk, but she understood it was a confusion in the simple English they were learning. The trade was established. They used to sit in a circle at their breaks and sing snatches of English songs they were learning “Spring is coming, spring is coming, all the little bees are humming”. One man picked up my little brother who had long blond hair and danced with him in his arms saying “I am going to take him back to Germany”. I ran in, in a panic, thinking he was going to finally show his true Nazi qualities, but my mother was watching from the gate and just took my hand. Peace had arrived, and with it my little brother’s epilepsy, and a polio outbreak which raged around the area. That vision of blue sky, red flowers and green grass has stayed with me all my life – I always dream of peace. But I know now it’s the one thing you never get – that dream cannot be realised.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

CHAPTER FOUR

NEW CROSS

Despite my months of experience I felt like a new girl at school reporting at New Cross. To begin with it was the second biggest tram depot in London - only very slightly smaller than Holloway in north London - and there were no trolleys but far more tram routes: 36, 38, 40, 46, 52, 54, 68, 70, 72 and 74 and several of these routes shed the plough and went on the overhead wires outside the central area and I hadn’t needed to do any pole swinging at all at Wandsworth. The duties started and finished at different times too - the first sign-on at New Cross was 03.19 and the last tram before the night service took over reached the depot about half an hour after midnight.

Although everyone was friendly and helpful the depot was so big that there were more crews on the spare list than on the entire rota at Wandsworth and the depot was older and seemed so vast I got lost several times in the first few days. There were all those new routes to learn, new fare tables with strange stage numbers to memorise and there was more bomb damage too, which meant that landmarks had been removed. Discovering where I was along the routes was so much more difficult. A study of any London Transport fare table will show that the stages are named after well known buildings - mainly public houses and churches, thus acknowledging God and Mammon in more or less equal proportions - and when these buildings were reduced to rubble by bombing I found myself having to ask the passengers where we were even in broad daylight.

Even when new fare tables were printed the same names were duly recorded in the firm belief that every one would be rebuilt. Of course, this did not always happen, a fact that was brought home to me in a very amusing way. While working on the 68 and 70 routes through Deptford High Street I looked in vain for a certain public house known as the White Swan, not only could I not find it but there was no bomb damaged area along the stretch of road where it ought to have been. So, when a passenger asked for the White Swan I kept an eye on him and watched where he alighted. Sure enough it was just where I thought it might be but no White Swan anywhere in sight. Next day I picked up several people at the stop and asked them to show me where the White Swan was, only to be told that it was burnt down at least ten years previously and a small block of flats had been built on the site! For all I know, there is still a White Swan fare stage somewhere in Deptford to this day! Of course, not all passengers referred to the stops by their official names and I noticed that women tended to ask for certain shops while men asked for the nearest pub!

In time, of course, I got to know them all and the names of most of the side streets adjacent to the shops too, but I admitted defeat to one dear old soul who, when approached for her fare, asked, “How much is it?” When I pointed out that I was unable to tell her until she told me where she was going, she promptly replied, “I’m going to the doctor’s, dear. My legs are something chronic.” I patiently listened to her tale of woe, covering several visits to her doctor, the clinic and finally Guys Hospital - and right through an operation, apparently for the removal of varicose veins “such as the surgeon said he’d never seen before in all his born days,” when she suddenly jumped up, thrust tu’pence into my waiting hand, and, soundly telling me off for keeping her talking and nearly making her miss her stop, she tripped off the tram and across the road on her “chronic” legs and away down the street at such a pace I could only assume the surgeon at Guys Hospital had performed a miracle. Occasionally through the years I’ve had several people ask, “How much?” or “Is it still tenpence?” and I think of that old lady every time.

Now that I was working locally and able to work out the duties, I used to tell Gran when I would be going past the house and she would sit at the upstairs window and give me a cheery wave as I went past - till one night a bomb dropped across the road and shattered all the windows for several yards in all directions. The glass was replaced by thick tarred paper boarding which solved our blackout problems for the rest of the war and meant living in artificial light except in the warm weather when we could open them for light and air. Luckily, though, that was the nearest we got to being bombed ourselves and did me one good turn. Of course, we had an Anderson Air Raid Shelter in the back garden but, as it was always two feet deep in water in anything but the height of summer, we all huddled under the stairs when the siren went and the raiders were overhead. The elderly lady who lived on the top floor was very deaf and I used to dash up and bang on her door till I woke her up, then down to tell Gran to hurry up. The family in the basement always used to come to the ground floor too, they were scared of being trapped should the rest of the house collapse. But my Gran was obstinate - she would insist on getting dressed, fully dressed, and when I remonstrated I always got the same reply, “If I’m going to meet my Maker it’s going to be properly dressed, with my stays on.” So I’d wait fuming outside her bedroom (she scorned all offers of help - did I think she was a child or something?) till she emerged, fully dressed, corsets and all. The bomb which demolished several houses across the road exploded within minutes of the alert siren and with no guns to herald its approach and from then on Gran decided her Maker would have to accept her in her night-dress and dressing gown like the rest of us.

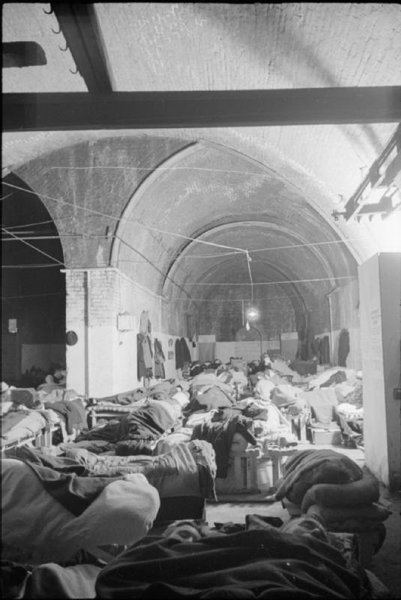

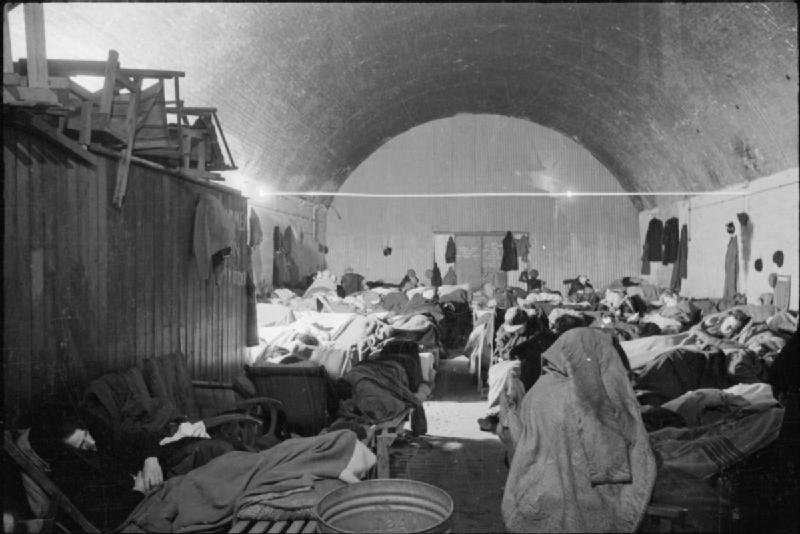

Thousands of people spent years sleeping every night in the Underground stations but they had to go there, with bundles of bedding and flasks of tea, quite early in the evening to bag one of the metal bunks which lined every platform - late comers slept on the platform itself or on deck chairs which also had to be carried through the streets or heaved on to a bus or tram. Our nearest Underground was at the Elephant and Castle, about a mile away, and Gran wouldn’t go that far so it was under the stairs for us night after night while the shells went up and the bombs rained down till it seemed we had been spending our nights this way all our lives. We still managed to do our day’s work, spending hours queuing for meagre rations, making do with powdered milk (not too bad), powdered egg (ghastly stuff but we ate it when our one real egg and two ounces of meat a week had been eaten), saving our precious clothing coupons and buying clothing for warmth and durability rather than style and fashion. But we were all in the same boat, united against a common enemy and the kindness and generosity I received from complete strangers made it all worth while.

Of course, the air raids weren’t the only hazards we had to face while working on the trams, the weather could play some nasty tricks too - especially the fog. There was no Clean Air Act in those days and, with factories going full blast twenty four hours a day and people burning everything they could lay their hands on when coal became short, we used to get some awful fogs in London - real pea-soupers, they were. When the driver could no longer see the track in front of the tram he would slide open the door and walk through to the back platform to ask for assistance. Then we would light the flambeaux or torches provided by the Board for just such an emergency. These torches were stout pieces of wood, about three feet long, bound with rags that had been soaked in some flammable substance. The driver would light the rags with a match and the conductor would then walk in front of the tram (or bus) waving the torch to indicate that the track ahead was clear. The old tram would grind and creak along behind at a snail’s pace and the driver and conductor knew they were going to be several hours late finishing that day or night. At least we were free of the air raids in the heavy fogs and that was some small comfort but the cold got to your bones, and your eyes were red-rimmed, straining to see through a mixture of fog and the smoky fumes from the flambeau. It was an eerie sensation, feeling your way through the choking fog and hearing sixteen and a half tons of tram moving close behind.

I must have walked miles like this in the two winters I spent in New Cross and several times an incident would occur which would break the monotony. One night we were proceeding through Deptford, near Surrey Docks, not a very select neighbourhood at the best of times. I was a few paces in front of the tram and we had been gliding through the fog like this for about an hour, when suddenly I got a shout from the driver, “Come on back, mate - we’re stuck - dead line.” I turned to retrace my steps and saw - nothing! No tram, no pavement and no sign of people - just thick yellow smoke, the oily flame of the torch in my hand and silence so deep you could cut it with a knife. I feared I had wandered off the track and held the torch nearer the ground to check but no, the rails still gleamed faintly in the flickering flare. Then a rattling chain and the thump of the platform steps dropping reassured me and I knew the driver was descending from the platform and coming to join me. I breathed a deep sigh of relief and walked a couple of steps back, almost colliding with the driver, and now just able to see the faint outline of the tram looming over us - but all the lights were out. “Better light another flare and prop it up the back - we are more likely to be hit from behind than in front,” said my mate. So through the tram we went, torch aloft, and lit a second one which we wedged between tram and buffers, making sure it slanted away from the paintwork. Meanwhile, the driver told me that there was no juice and we would have to wait till the electricity supply came on again before we could continue. “The last time this happened to me was when some idiot driving a lorry mounted the pavement and crashed into a substation,” he said.

Damage to a roadside substation cuts the supply of power to only a small section of road and the usual procedure is to wait till the engineers come along to fix it and send us on our way. But at 10 p.m. and in the thickest fog for years, how long was that likely to be? A friendly shout and measured footsteps heralded the arrival of a policeman, his black mackintosh cape dripping with condensed fog but a wide smile under his helmet. He told us he had been warned to look out for us. The driver had guessed correctly - it was a bus that had crashed into the substation box and rendered our stretch of line dead. “Can’t stop, mate,” he said, “Got to keep the next tram from running too far - they’ve got through on the phone to your chaps so they will get here as soon as they can.” So with that much information we had to be content and returned to the tram.

It might be just slightly warmer inside, we thought, but if it was we hardly noticed. We carefully counted our cigarettes - only five between us to see us through what looked like being a long night but we lit up just the same. We talked about the war, the job and our families and stamped up and down the tram trying to bring the circulation back to frozen feet and numb fingers. Our last passenger got off several stops past and we were beginning to think we were the last people left on earth when a faint call sent us hurrying back to the platform. There stood a man I recognised as one of the regulars who used the tram to travel back and forth to his job in the docks. “The copper just told me you were stuck here,” he said, “I’ve brewed up a pot of tea and stirred the fire up - only live round the corner - come on round and have a warm up.” I felt I could have hugged him but we couldn’t both leave the tram. No vehicle may be left unattended, even in these dire circumstances, so, like a true hero, my driver insisted on me going first. “Don’t worry, love,” said our saviour, “You won’t be all alone with me. I’ve got the old woman up.” And so it was.

The entire family of mother, father and four children lived in one room under appalling conditions. The children curled up in both ends of a single bed and the parents in a camp bed in the opposite corner. What with a kitchen table and chairs, a dresser and wardrobe cupboard and lines of washing across the room there was hardly room to move but all I saw in that first glance was the glow of the fire piled with tarred wooden blocks with flames leaping up the chimney. “Bit of luck, that,” said my escort, “They’ve just finished mending the road outside. Those tar blocks burn a treat, don’t they?” I had to agree. I wouldn’t have cared if he were burning the wooden seats of the tram right then; I was so glad to sit there in the high backed wooden armchair and watch steam rising from my clothes. “Let me pour the girl a cup of tea, Bert,” said my hostess. “Do you fancy a bit of bread and dripping, ducks?” Would I? But what about the rest of the family? A glance around the room told its own story. There wasn’t much money to spare in this household. My four pounds a week wages was probably much more than the breadwinner was getting to keep his family of six and they were offering me what was probably part of their breakfast. But I had no real choice - it was quite obvious that an offer to pay would have deeply offended them and a refusal might have made them believe I thought myself too refined for such humble fare. So down went the doorstep of bread and dripping between sips of hot tea from a slightly chipped enamel mug and it was wonderful. I knew I would have to go soon - I couldn’t forget my driver, still out there in the fog while I was warm and fed, so I got the tea down as soon as I could, but it was hot and Bert and his miss's were chatting away, mostly about their children.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

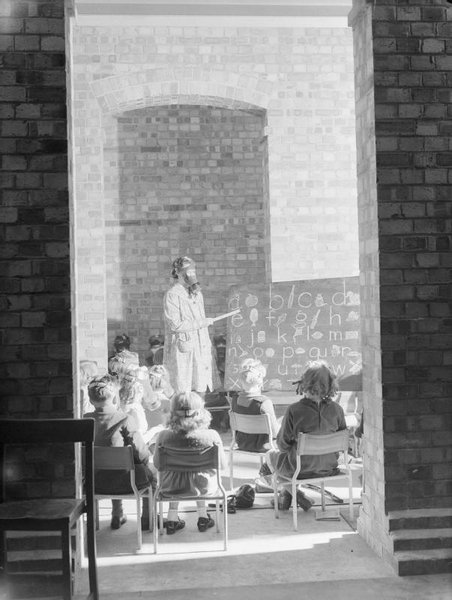

They admitted they should have sent them away when most of their mates’ kids were evacuated but they just couldn’t bear to part with them. The schools were closed down and they weren’t getting any education but the three boys were expecting to work in the docks like their dad and you didn’t need much education for that - not the kind the schools provided, anyway. Neither of the parents could read or write very much and the family had been dockers for generations so who was I to suggest they might aspire to higher things. No one could have been kinder than those two and when someone offers all they have to a complete stranger that puts them in a class above any other, in my opinion. I asked Bert if he would see me back to the tram so I could allow my driver to return and he was glad to see the pair of us. Then Ada turned up, “Don’t like to think of you out here all alone, duck,” she said. She had muffled herself up against the cold and followed her husband out into the cold fog to keep me company while my driver had his tea and a warm by the fire.

In the next quarter of an hour I had heard all about the children and how they could pick up a few coppers helping out in the local shops, doing errands for the old people and tackling a morning paper round. It must have been a happy family for all their poverty and I managed to get her to accept a shilling each for the children “From their new Auntie Doris,” I said. Apparently counting oneself as a member of the family made it quite acceptable and I didn’t feel so guilty wolfing down the bread and dripping after that. We had a cigarette and chatted on till my driver came back. We thanked our new friends once more and watched them disappear into the fog. It was after 11.00 p.m. by then and we knew the repair gang hadn’t mended the substation for we were still in the dark. They finally arrived about twenty minutes later and ten minutes after that we were on our way.

I walked ahead for about twenty minutes longer, picking up one or two passengers as the pubs turned out. It takes more than a London pea-souper to keep some blokes from their favourite hobby, it would seem. My first contact with these few “rabbits” would be when I almost cannoned into them along the track. Of course, they heard the tram coming and simply walked into the road towards it, swinging on as it crawled past at a snail’s pace. After the first couple I ticked my ticket rack into my moneybag and issued tickets on the road to save myself the effort of climbing on the tram each time. A couple of chaps must have come straight off the pavement and on to the tram without passing me, still plodding away in front, and I found their few coppers fare on my locker top under the stairs. People were very honest in those days and the poorer people were the more honest they were, it seemed. I think it was a matter of pride more than anything else was. You had to prove you could manage without getting into debt or asking for charity. In fact, charity was a dirty word to most working people - much dirtier, in fact, than some four-letter words bandied about today.

Hire purchase was becoming available for some goods but most people, especially the older ones, considered it not quite respectable to possess goods before they were paid for. My Gran always held these views and would go without rather than buy things “on the never-never”. She made me save part of my pay every week till I had enough cash to refurnish my room and start a home of my own. When I had the magnificent sum of seventy pounds in the bank, she took me along to the dockside warehouse and for sixty nine pounds cash we chose all my furniture - bed, large wardrobe, man’s wardrobe and dressing table in walnut (veneer), dining table and four chairs in fumed oak, settee and two armchairs in imitation leather known as Rexene, a twelve foot by twelve foot carpet square and fender and fire-irons for the fireplace. They lasted for years and years, in fact, I still have the wardrobe and dressing table and I’ve been married thirty-six years now. Our sense of values has certainly changed in that time till now the use of credit is regarded as normal and fare dodging, especially by the younger generation, has become the subject of self-congratulation rather than shame. I wonder why?

Of course, children didn’t use Public Transport much in the War, those children still living in London only rode on buses and trams when they were taken out by their parents for a treat. When the authorities realised that thousands of children had either never been evacuated or had returned to London the schools began to open again but the children walked to and from school as they had always done. There were no special school journeys as there are now and bus crews weren’t bowled over by a screaming, fighting and even cursing horde of school children twice a day as they are now either. And the tricks those little darlings get up to in order to avoid paying their fare would certainly disgust their grandfathers who used to leave their fare on the tram because the conductor was walking in front with a torch!

By this time we had reached Greenwich and it was well after midnight, and the fog was clearing, thank goodness. Our last passenger swung off as I climbed wearily back onto the platform. There was quite a long line of trams gliding through to New Cross, some from Catford, Lewisham, Brockley and Woolwich and we all carried on in convoy to the Depot. Then, after queuing up to pay in we dispersed outside the Depot and went our different ways home to sleep through what was left of the night. Of course, the night trams were running but all well late so I started to walk down the Old Kent Road rather than wait at New Cross Gate till one arrived. I heard it coming as I approached Canal Bridge and rushed out in the road to swing aboard. The driver pulled up right outside 234, saving me walking round the corner, and I was straight up the steps and into the house like a rocket. Although the fog came up again several more nights, it never got quite bad enough to make me get out and walk and it was weeks later when I was working in fog again and I had another incident which always raises a laugh when I retell it (which is probably all too often).

Although the fog was pretty thick on the Embankment, the driver told me not to bother to walk in front. The fog always hung heaviest along the river and it would clear up once we left the water behind us. It was quite late at night and I knew I should have to leave the tram to pull the points over at the crossroad the other side of Westminster Bridge. At all main crossings a pointsman sat, pulling over the points so that each tram went off in its proper direction, but once the evening rush was over and the pointsman finished for the day, then all point pulling had to be done by the conductor. Each tram carried a points lever, four feet long and made of iron. It took a bit of lifting across to the pavement - there it was fitted into a slot and pulled across to send the tram around corner. The lever had to be held against the tension of a heavy spring while the tram passed over the turning points. Then the lever was released allowing the points to return the track to the straight ahead position and the conductor pulls the points-iron out of the slot and dashes round the track to re-board the waiting tram. I had repeated this manoeuvre at lots of crossroads without any mishap so what happened on this night was completely unexpected.

The driver pulled up at the usual spot and I alighted with the points bar and crossed to the pavement. The fog was rising from the river and swirling round my feet and it took me a little time to find the slot in the pavement and insert the iron bar. I strained to pull it across and felt the spring points engage. “Okay, mate - full ahead!” I yelled and the tram pulled away and I hung on to the bar. It was damp and threatened to slip from my grasp. I knew if I let go while the plough was slipping from one track to the other then the plough would buckle and the tram would be in a position with the front wheels on one track and the rear wheels on another. The mind boggles! I desperately hung on and breathed a sigh of relief when I heard the rear wheels crash against the points and continue round the corner. For some reason the points-bar seemed jammed and I tugged it first one way and then another till finally it jerked out of the slot, nearly throwing me off my feet. I looked to where I thought the tram should be waiting and saw nothing but fog so I started walking along the pavement, peering hopefully into the road, still looking for my tram - still nothing but fog. I began to hurry faster; surely I should have reached the crossroad by now?

Walking along the pavement and staring into the road I collided violently with a gentleman dressed in blue serge and found myself looking up into the bearded face of a tall policeman.

“Oh, good!” I exclaimed, “Have you seen a tram?”

“Hundreds,” was the unhelpful reply, albeit accompanied by a twinkle in his eye and a broad grin. “Now, what’s the trouble, young lady?”

“I think I’ve lost a tram,” I replied, plaintively and the grin melted into a chuckle and the chuckle into a roar of laughter. I began to see the funny side of it myself by then and we both laughed and I nearly choked trying to explain and stop laughing in one breath. Now, don’t ask me how I’d managed it, but I’d not only started walking in the wrong direction but even managed to cross the road without realising it and we were both standing just under Big Ben, a point emphasised when it boomed out the half hour chime right over my head.

So, held firmly by the elbow, I was marched across the road and over the bridge again to be met by a bewildered but very relieved driver who had broken the golden rule and left his vehicle unattended to look for his scatty conductor. The laughing policeman insisted on staying with us till I was safely back on my platform and when the passengers were told what had happened they rocked with laughter too. Was my face red! “Well I’m certainly glad we found you alright,” said my friend in blue, “I’ve never had to report a lost tram before.” We made up the time before we finished the duty so I didn’t have to fill in an official report - but the story soon got around and I wasn’t allowed to forget it for the rest of my stay at New Cross Depot.

The days of Winter eventually gave way to Spring and now it was lighter in the evenings and people went out more, the air raids slackened off for a while and the sale of sixpenny evening tickets went up by leaps and bounds, whole families would sally forth to visit relatives they hadn’t seen for months and many a romance blossomed on the top deck while we bowled along the country roads of Bromley, Grove Park or Abbey Wood. We were even busier all day Sundays and when the Easter Bank Holiday Monday arrived several extra trams had to be pressed into service to cope with the queues of passengers at almost every stop. Despite the long list of spare staff in the Depot, the call went out to all depots to ask for volunteers to do overtime and rest day working throughout the holiday weekend. People came out in their thousands to visit Greenwich Park where they spent the day picnicking on the grass or sitting round the bandstand listening to the brass band or walking through to Black Heath to the Fair.

It was, of course, traditional in those days to buy new clothes for Easter and very smart and happy they all looked too. Working people only had two changes of clothing then, one for best and the other clothes they wore to work. Every Easter out came the carefully saved up clothing coupons and a new best outfit chosen. Children’s clothes were usually purchased one or two sizes too large to allow for growing and mothers were busy just before Easter putting deep hems on dresses and trouser legs and taking in side seams with big stitches they could easily unpick the following year. Cotton wool would be stuffed into the toes of boots and shoes that were a couple of sizes too large and last years best brown shoes would be sent to the menders (or resoled and heeled at home) and dyed black to smarten them up for another year’s wear at work or school. When money and coupons ran out, linen hat-shapes would be purchased at the local draper’s and covered with pretty material costing about one and sixpence a yard, half a yard would be plenty for one hat, so two sisters or mother and daughter could have new hats at a cost of half a crown (twelve and a half pence) the pair.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

Now I was attached to New Cross Depot I had to work late Saturday and early Sunday duties, which meant walking from home to depot and back. I don’t know which I liked least. There were still quite a lot of drunks about after a late night Saturday duty and after at least eight hours on my feet I’d be dog tired but I hurried along as fast as I could - never having to put up with anything worse than a few whistles and occasional shouts of “Fares please” or “Look out lads or she’ll give you a fourpenny one.” For all that I was glad to close the front door behind me and practically fall into bed.

The rotas started at 6.00 a.m. on Sundays, so the walk to work would often be in the dark too. I remember one Sunday morning in particular. There was a full moon still and the streets were quite empty with only the sound of my own footsteps till I got about two thirds of the way then, just as I was passing the gasworks where the old asylum and workhouse building still stood I became aware of another sound of footsteps behind me. Thinking it might be a friendly copper who would be company to talk to while working, I turned round and found myself looking into the face of a big Negro. The moon was shining, lighting up the whites of his eyes and flashing teeth. I was terrified. It might seem rather odd now, but the fact remained that I had never seen more than on or two coloured people in my whole life before and this man was huge and very, very black. Poor man, he must have seen how scared I was - he called out, “Please don’t be frightened, miss. I’m only walking to work - same as you. Would you like me to stay behind you or shall I walk in front?” The kindness and understanding he showed me made me feel thoroughly ashamed of myself and I waited till he got a little closer and told him I would rather have company to talk to while I walked if he didn’t mind. So the friendly black giant and I walked down the road to New Cross where he - gallant to the last - saw me across the road to the gates of the depot before continuing on his way. I know a lot of people resent the influx of thousands of coloured people into our society in recent years but, at least, people are no longer scared just because they have darker skins than we do. That can’t be a bad thing surely?

The summer slowly passed - then the autumn and my second Christmas on the trams approached. Of course, we had to work but we were guaranteed one day off over the Christmas period - either Christmas Day or Boxing Day. All trams were back in the Depot by 4.30 p.m. on Christmas Day - early turn workers doing a full eight-hour shift and being paid for sixteen hours, the late crews only did half a duty and paid for the whole day. So for Christmas 1942 I struck lucky - my normal day off fell on Christmas Eve and I was scheduled for a day off on Christmas Day, so I was able to go over to Staines to deliver my presents to my own family and Bill’s family too. I thought my mother-in-law rather subdued, but I knew she was worried over her sons - Bill in the Navy and his elder brother, Stan, in the Army with young Frank still at school and longing to be old enough to join the RAF. I wanted to be back in London before dark if possible so I wished everyone a Happy Christmas and went back to Gran.

We had another addition to the family now, Uncle Harry — my father’s older brother — who had left his job in a hotel on the coast and now worked in London. The air raids had eased off in the last few weeks otherwise Harry would not have returned. Badly shocked in the trenches in 1917, he was still very nervous and apprehensive, unable to hold down any job calling for responsibility and initiative, he worked long hours as a kitchen porter, the butt of his work-mates who mistook his nerves for stupidity and were constantly taunting him, calling him “Dummy” and remarking he was “only ten to the dozen” or simple minded. It was a great shame, he was a very shrewd man really — and provided you had the time to listen and wait while he collected his thoughts between sentences — he was very interesting to talk to. The casualties of war are not only the dead and maimed and I prayed that Bill would get through without suffering like poor Uncle Harry.

Of course, I should have liked to have heard from Bill but there had been no letters for some days. Not that this was particularly unusual, we wrote to each other every single day but, of course, being constantly at sea his letters tended to arrive in bulk weeks apart. I kept all his letters for years after the War — they nearly filled a small suitcase — but finally destroyed them when several went missing in a very amusing way. My two eldest children decided to play postman. They must have seen me reading the letters from time to time and knew where they were kept, and the first time I knew anything was amiss was when several neighbours knocked on the door to return them — the children had delivered about a dozen all down the street! I didn’t have the nerve to knock on doors and ask for their return. We all sat up to see the New Year in and hoped that 1943 would see the War over, it had been raging for over three years by now and we seemed no nearer the Victory we all longed for.

A few days later in the early morning there were two knocks on the front door — thinking it was the postman, I rushed downstairs to open it and there was Bill. It was wonderful to see him again, but he looked very drawn and pale and I suddenly realised he was in a completely new uniform with no badges on his sleeve — even his collar and cap were brand new, and I suddenly realised he must have lost his ship. We hurried upstairs to tell Gran and Uncle Harry the good news that Bill was safely home again and sat listening to his explanation. It was awful — HMS Partridge had been torpedoed and sunk in the Mediterranean on my birthday, December 20th. After several hours swimming around in the oil-covered sea, Bill was picked up by another destroyer and taken into port. Clothed in whatever garments the crew could spare, he and a few other survivors were later transferred to a troop ship that finally delivered them safely to this country. Then followed a day of re-kitting from scratch — the only thing he owned when he arrived in this country was his identity disc around his neck — everything else was at the bottom of the sea, somewhere in the Mediterranean. His greatest loss was of his mates, though especially “Shady”, a boy who had gone through training school with Bill right from the time he had joined up. I suppose the one who understood most of all was Uncle Harry. He couldn’t say very much but he knew what it was like all right.

Of course, I dashed off to ring the Depot. When the Depot Inspector heard that Bill was on survivor’s leave he told me to ring again in a week’s time. I saw the sheet later — I had been covered for every day that week and had five crosses which meant I had lost only two day’s pay. Of course, Bill wanted to see his mum, and, as he had to wear his uniform, I spent that evening sewing on the new badges and hoped there would be no more raids while he was at home. He was very shaken and restless and could talk of nothing else but seeing the ship breaking in two and each half going down, taking so many men with it, the sea covered in burning oil and hearing his rescuers calling him to grab the rope and almost drowning in his panic because he couldn’t see it with his eyes covered in black oil.

Bill’s mother was overjoyed to see him and laughed and cried together — I had never seen her like this before — usually a very quiet, reserved woman — I had misjudged her, mistaking her calmness for a cold nature. Then I was told why she had been so subdued on my last visit on Christmas Eve. She had been listening to Lord Haw-Haw, the traitor who broadcast from Germany — and he had reported the loss of Bill’s ship. Of course, a great many of his reports were propaganda and had no truth in them, they were aimed at breaking our morale. His call sign was “Germany Calling” and thousands of people used to tune their wireless sets to listen and then pray that he was not telling the truth, especially if their loved ones were involved in the disasters he described. On this occasion he had been telling the truth and my dear mother-in-law had not mentioned it to me for fear of spoiling my Christmas. I’ve often wondered if I could have been so thoughtful for others under similar circumstances.

We spent that week visiting members of the family. Gran wondered if it was good for Bill to be constantly telling people about his experiences but I noticed he slowly began to grow calmer and less jumpy and decided it was probably helping — to be able to talk about it and get it off his mind: till the day we went to the cinema. I had carefully chosen a programme of comedy films but had forgotten the newsreels. We saw a convoy of ships crossing the Atlantic, suddenly one of them opened fire and Bill was out of his seat and several steps down the aisle before he remembered where he was. Survivor’s leave was always twenty-one days and now I know why. It wasn’t long enough but the men couldn’t be spared for longer than that. Of course, I had to go back to work and the weather was not particularly good but Bill was feeling better all the time and soon he began to laugh and joke again and I began to think of the future and what I would have done if he had not returned.

Then we had our first argument — not a row — but a real, definite difference of opinion. I wanted a child and Bill was totally opposed to the idea. Of course, I could see his point of view — he believed that, if he did not survive the War, I should find it very difficult to find another husband and eventual happiness again if I had a baby to bring up. I absolutely rejected the possibility of ever replacing Bill with another man and, if I lost him, I wanted more than just a framed photograph and a bunch of letters to keep his memory intact. We have relived this argument several times over the years when discussing the situation with friends and relations and almost invariably the men have agreed with Bill and the women have decided that their view would have agreed with mine. So it would seem that the difference between men and women isn’t merely physical after all.

After the first week I had to return to work and Bill would often spend the day on my tram. He found that he rather liked the job and the happy atmosphere in the Depot — several of the older drivers had served in the Navy in the last war and he enjoyed exchanging yarns with them, and I think he was a little surprised at the way I had blossomed out too. He was used to a rather timid and painfully shy girl and here she was — chatting merrily to passengers completely in her element. There was no doubt that I loved my job and would be sorry to have to leave when the War ended.

All too soon the day arrived when he had to report to Chatham again and we started the old routine of writing every day and looking forward to Bill’s next leave.

After a few weeks I was able to confirm my suspicions and write to tell him I had won the argument after all and he could expect to be a proud father in late September. He was thrilled — and so was I when he told me he was still not at sea but at Scarborough, with a proper civilian address. It was much more pleasant addressing my letters now, “c/o GPO London” was so impersonal. His landlady was very pleasant too. For the one and only time I cheated — I went to the doctor with a very mild sore throat and got a certificate for three days. It was a lovely weekend — but Bill had to tell me that his stay in Scarborough would not be a long one — he was just waiting for his new ship and would be off to sea very soon — North Atlantic Convoy Duty.

We were sure the baby would be a boy and decided he would be called Michael and always referred to him by name in all our letters from that weekend. I hadn’t told anyone at the Depot that I was expecting a baby and kept the secret as long as I could but, despite several alterations to my uniform, there came a day when I could no longer push my way past standing passengers in the rush hour and I had to give in my notice. I was persuaded to apply for Maternity Leave — just in case I felt like getting a relation to look after the baby and returning to my job. I’m very glad that it didn’t occur to me at the time that they were really making it easy for me to return in case anything should go wrong — such a thing never entered my mind. I used to sit at the open window waving at the trams as they went by all through August and September and on October 10th the baby arrived — our son, Michael.

Contributed originally by addeyed (BBC WW2 People's War)

Iwas born in 1930 in Dulwich,the youngest of four boys. My parents moved to a new house in Grove Park South London after I was born.My mother died there when I was 18 months old.I was sent to live with grandparents until I was four years old when my father remarried. When the war began in 1939 I was evacuated with Baring Road primary school to Folkestone. My eldest brother had joined the Army in 1938 and was in Palestine with the Royal Dragoon Guards cavalry. The other two boys stayed at home with my father and stepmother. My father had been gassed in France in the first world war but worked as a hairdresser in New Cross. When the owner retired in 1940 my father bought the shop and sold the house in Grove Park. The family moved into the flat above the shop in New Cross Road.In early 1941 with the occupation of France by Germany and frequent enemy air raids over the South Coast my school was sent on to the safety of South Wales. I found myself living with the local milkman and his mother in a tiny cottage in Tredegar, Monmouthshire.They were very kind to me and I enjoyed helping the milkman with his deliveries in his pony and trap at weekends.He took the milk round in large metal churns and the housewives would come out to the vehicle with jugs to be filled. I stayed with Bryn Jones until I passed the 11plus school examination and was given a grammar school place.Since my family now lived in New Cross I was sent to the local grammar school Addey and Stanhope which at that time was evacuated to Garnant, Carmarthenshire.I was very sad to leave my schoolfriends and my fosterparents and even more so when I arrived at the dingy mining village which was Garnant. I found myself billetted with an elderly spinster who taught piano in her front parlour on Sunday mornings after chapel. She was already looking after another young evacuee but he did not stay very long. The cottage had no electricity and lighting was by oil lamps which were carried from room to room. It was very eerie going upstairs to bed at night with shadows cast on the walls. Cooking and heating was by the use of a coal fire combined with a blackleaded iron oven range in the parlour.Since there was no indoor toilet or bathroom one had to use the privy at the bottom of the garden and wash in the scullery sink. Baths were taken in a tin bath placed in front of the open range with water heated in buckets. Friday nights were always embarrassing when my fostermotherinsisted on washing my back!

Meals were simple fare.Breakfast was porridge and toast (using a toasting fork and the open fire)and teas was bread and jam with a home made welsh cake. Ihad schooldinners except at weekends. On Sundays my fostermother boiled a sheep's head and made brawn eaten with boiled potatoes and cabbage.Tea was tinned paste sandwiches with a slice of cake.

I made friends at school and did quite well in lessons, but I felt very lonely in the little cottage with the elderly spinster as my only company.I read a great deal though the lamplight was never very bright. There was a crystal wireless set in the parlour but it was hardly ever switched on.Miss Williams never bought a newspaper so I did not learn much about how the war was progressing. I had only an occasional letter from my father in which Ilearned that my eldest brother's regiment had exchanged their horses for tanks and were fighting in the North Africa Desert campaign. My two other brother had been called up and were both in the Navy.I did not hear from them at all.

Ihad to attend chapel three times on a Sunday with Miss Williams and since the services was mostly in Welsh I found them long and tedious until I learned a little of the language.One thing could not be denied-the Welsh locals enjoyed singing and the choirs were extremely vocal!

On Saturdays I would run the odd errand for my fostermother,going to the small shops in the village for groceries. During the summer I would fish in the small brook that run past the village with the aid of a homemade rod and line made from a small branch, a piece of string and a bent safety pin which served as a hook. Worms or a piece of bread served as bait. I rarely caught anything in the stream but it helped pass the time.Other days I would climb up the waste coal tip that rose up behind the cottages and slide down it on a battered old tin tray. It was good fun but often I went back home with grazed knees and grimed clothing which did not please Miss Williams. She preferred that I went and picked whinberries from the bushes that grew on the slopes of the steep hills that surrounded the Welsh valley and I must admit I was very fond of the pies my fostermother made from this wild fruit!

My life continued in this fashion until early March 1943 when a fellow pupil approached me in the school playground and told me my father was dead. Shocked, I asked him what he meant. He said that he had heard Miss Williams tell his fostermother that she had received a letter from my stepmother saying so and that I would have to go back to London. When I returned to the cottage after school I asked Miss Williams if the news was true.

She denied having received any letter and knew nothing about my father. The next day I caught the informer in the playground and called him a liar. I was always a easy tempered boy and never got into fights but I was so angry I punched him in the eye and knocked him down. He still insisted that his story was true.

When I returned to my billet after school I again asked my foster mother if my father had died. "N0", she said, "But it is true that I have had a letter and your parents want you to go back to London." "Why?" I asked. "The war is not over yet". "I expect they just want to see you"Miss Williams said. "You have been away a long time.I am sure you want to see them. After tea I will help you pack.Tomorrow I have to put you on the bus to Neath to catch the train to London.Someone will meet you at Paddington station.

With my head in a whirl I watched Miss Williams pack the few things I possessed in the battered old suitcase I had carried from London five years before. She made me kneel on the floor beside the bed to say my prayers as she always did and gave me a hug as I climbed between the sheets.In the dim light of the lamp I thought her eyes shone quite wetly. "Sleep tight,"she said "You will have a long day tomorrow."

I could not sleep. Everything was happening too fast and despite Miss Williams reassurances I was beginning to doubt that she was telling me all she knew. She had refused to show me the letter she had received and I suspected it contained news that she wanted to keep from me.

Early the next morning, after breakfasting on a boiled egg which I found hard to swallow Miss Williams took me down to the bus stop and we waited for the Neath bus.

When it came my foster mother gave the conductor my fare and asked him to make sure I alighted at Neath railway station. Then she gave another hug. "Don't worry, Jimmy," she said "Everything will be alright". This time I could see the tears in her eyes. She stood there waving as the bus pulled away. It was to be my last sight of her.

I alighted at Neath without any trouble but I was shocked when the London train pulled in.It was packed to capacity. All the compartments were full and even the corridor was crowded with standing passengers, many in uniform with haversacks, gasmasks etc. I had to squeeze along until I found a tiny space where I could put down my case and sit on it.I had been told that the journey would take about four hours. Even surrounded by chattering people I suddenly felt very much alone.

The train seemed to stop at quite a few stations, disgorging military personnel and civilians, all seemingly in a haste to get to their destinations, but with their places taken by others so that that there was always someone standing above me. I was a very small thirteen year old and felt it.

This was a different world to the village life of Tredegar and Garnant where the war seemed far away. The uniforms of American, Free French and Polish military personnel

mingling with British uniforms, and the unfamiliar tongues I could hear in conversation were a stark reminder that this small island had become a gathering point for the impending invasion of Europe. I wondered where my three brothers were and if they would survive the conflict. The thought led me on to wondering about my father. The nearer I drew to London the more I became convinced that my quick dispatch from Wales meant that something dreadful had happened at home, and it seemed probable that the boy in the playground had not lied to me. I tried to dismiss the idea from my mind but my heart was a dead weight in my chest.

As the train pulled into Paddington I stood up and tried to glance through the grimy windows. I had no idea who would meet me. Surely it had to be someone I knew and who knew me and yet I had seen none of my family in five years. Slowly I alighted from the train and found myself pushed and prodded down the platform by hastening passengers. Through the barrier I stopped and looked around. There were several groups of people standing around and others standing alone. I did not recognise anyone.

I took a few more paces forward anxiously scanning every face. No-one seemed to be looking at me.Suddenly Iheard a voice behind me "Jimmy? Is that you Jimmy?"

I turned, startled. The man was tall and lean in an Army uniform, medal ribbons on his chest. My heart jumped. "Bill?" I stammered "Hello,old son" The soldier grinned down at me."I was afraid I'd missed you. Give me your case. We will catch the bus outside." With that he took the case from me and with the other hand lightly clutching my shoulder he led the way briskly out of the station. I kept glancing up at him,hardly believing my eyes. He was so smart,so handsome, so manly! I had not seen him since 1938.The last news I had of him was that he was in Italy fighting near Monte Cassino.What was he doing here? I was afraid to ask.

We boarded the bus for New Cross and on the journey my brother asked mundane questions about life in Wales and my school.He never mentioned our father and though the question was on my lips I dare not ask it. It was not until we we walking towards the hairdressing shop that I found the courage. "Bill. My dad. Is he,is he,dead?"

My brother stopped. Turned towards me, looked down at me. His hand tightened on my shoulder. Gravely he said "Yes, Jimmy. I am afraid he is."

My eyes filled with hot tears.I blinked, brushed them quickly away. I had known the answer before it was spoken but it still hit me like a kick in the stomach.My mind then froze over and I could think of nothing more to say.If Bill said anything further to me before we arrived at the shop doorway his words did not penetrate my brain.

My stepmother Winifred was waiting to greet me in the flat above the shop.In appearance she was much as I remembered, tall and slim with her black hair parted in the middle so that it resembled a pair of raven's wings. She was dressed all in black but she wore her customary bright red shade of lipstick that matched the colour of her impeccably varnished fingernails.As I appraised her I felt the same nervousness that had always gripped me in her presence. She had always been a strict disciplinarian in the home and exercised strict control over my brothers and myself. Any wayward behaviour from us was met with swift chastisement, often physical, with the use of any instument that lay to hand. We soon learned not to defy her wishes.There had been no point in complaining to Father. His contaminated lungs made him cough and wheeze and he did not possess the physical or mental strength to enter into arguments with his new wife.Our guess was that not only had he been attracted by Winnie's allure but because as a nursing sister she seemed an ideal candidate as a wife and carer of his children. He was not to know that she did not have an ounce of maternal instinct within her body.He was unaware of Winnie's cold dispassionate attitude towards us for she did not show it in his presence.We loved him enough not to add to his burden. Our stepmother was all sweetness and light when he was home,which was only on Sundays in daylight hours. During the week he left for work as we were preparing for school in the mornings and usually arrived home after we had been put to bed in the evenings.By that time he was physically exhausted and only had the energy to put his head round the door of our bedroom to see if we were asleep.

The commencement of war in 1939 put an end to our torment. Though I was sorry to say goodbye to my Father I was thrilled to escape from Winifred's clutches and not be at her continual beck and call. Bill was with his regiment but I am sure Len and Fred

were both anxious to reach the age of call up so that they too could get away.

Now I was back under the same roof as our stepmother and at 13 years of age still under her control. I did not look forward to the future with much confidence.

Sitting in the small lounge of the shop flat that evening i learned that my father's funeral had already taken place. My three brothers had all been given compassionate leave to attend but Len and Fred had returned to their ships some days before. Only Bill had been granted extended leave because his unit had just arrived from Italy and was at the South Coast-preparing.as I found out later, for the D-Day landings in June. Within a few days he too had gone and I was left alone with my stepmother.

The following weeks passed slowly and drearily.Winnie kept the shop open with the asistance of two female staff who attended to the hairdressing needs of lady customers.Astonishingly Winnie took upon herself to give haircuts to men and proved quite competent at it. My role was to keep the salon clean, sweeping the floor and washing the handbasins etc.

Contributed originally by Harrysgirl (BBC WW2 People's War)

A few years ago I recorded several conversations with my parents about their lives. My mother was the daughter of a stevedore who worked at Surrey Docks. She was 16 when war was declared, and she spent the war years in Deptford, London, with her father and sisters. She is now aged 81. What follows is her account of her experiences during the war, which I transcribed from the tapes.

Daisy's War

When the blitz started when we were living in a terraced house in Greenfield St. in Deptford, and we had to have an Anderson Shelter built in the garden. The workmen brought it and they dug the hole and installed the shelter. Half of it was above the ground, but the floor was about four feet below ground. They fitted some benches, which were most uncomfortable, and water seeped in from the ground making it soaking wet most of the time, but we slept down there nearly every night throughout the blitz in 1940-41. At one time we didn’t even wait for the air raid sirens to go off because the raids were nearly every night.

There were an awful lot of houses damaged, and many of those that were not flattened had to be demolished because they were unsafe. When we went up the high street in the morning after a raid there were plenty of shops that had been hit and the big factory where they made parts for fire engines, was destroyed. The Surrey Docks were not far away, and one night they were badly hit. We could see the sky all red from the fires. My brother, Stan, had a friend who was in the auxiliary fire brigade and he got killed that night on the docks. It was very sad - his mother had already lost her other two sons and her husband to tuberculosis. On Blackheath, outside Greenwich Park gates, there used to be a huge hollow where the fair was set up every bank holiday. During the war they filled it right up with the rubble of the buildings that were destroyed, and now that part of the heath is flat.

Most of the raids were after dark. We didn’t always go down the shelters, but it was so tiring if the air raid warning went in the night. We three girls slept in one room downstairs. I was always on the end and I had to go tearing up the stairs to wake my father up and tell him that the alarm had gone, because he was deaf and didn’t hear the siren. Then we’d all go down the shelter. It was horrible to be woken like that night after night, and really tiring. We had a dog at the time and he soon learned what the sirens meant. For daytime raids, as soon as the back door was opened he ran out to be the first one down, and at night he slept there. Sometimes he took his bone down and woke us up gnawing away at it. Then we’d kick him to make him leave the bone alone.

The worst period was during the blitz, which lasted for 6 or 9 months overall. As the Battle of Britain went on the RAF knocked a lot of the bombers out of the sky, and then things were a bit better. On Blackheath there was a huge anti-aircraft gun called Big Bertha, which used to belt out at night, with batteries of searchlights trying to pick out the bombers. The searchlights all over the sky at night were spectacular to watch, until the sirens went: then we ducked down into the shelter. My father was usually the last one down, as he was deaf and stayed outside looking up at the sky, oblivious to the shrapnel falling all around and hitting the shelter roof. We had to shout at him to come down in case he got a lump of it on his head. I suppose quite a few people must have got killed with shrapnel.

The Air Raid Wardens were very hot on lights, and we dared not have even a streak of light showing through the curtains. Even outside there were no lights: patrolling wardens would shout “Put that fag out” if we so much as struck a match. We were allowed to use torches, but we had to be sure they were directed towards the ground. When we went out it was pitch black at night, all the lights were off and you had to have a torch in the winter.

Despite the bombing and the blackout we still went out in the evening during the war. We went up the West End sometimes on the Underground, where people spent the night if they had no air raid shelter. I first saw “Gone with the Wind" in the West End. If the air raid sirens went off while we were in the cinema the film just carried on -we never left. Strangely enough we weren’t frightened; maybe a bit wary, but not really frightened. Sometimes you could hear the bombs going off outside, but after a while we ignored it, more or less. We had guns from the cowboys going off inside and bombs going off on the outside. A lot of people got killed that way, especially in night clubs, by not leaving during the air raids.

If we were caught in the street during a raid, it was a different matter – we ran for the nearest shelter. We always ran for cover if we were outside. In Deptford High Street there was a bomb shelter under a big shop- Burton’s, a clothing shop. Everyone out in the High Street when the sirens went off ran for that, and stayed down there until the “all clear” sounded. Most of the raids were at night, and in the morning on the way to work we could see what the bombs had done . The did a lot of damage - knocked down buildings, shops and everything, but Burton’s was never knocked down. There were some American troops in the area and they used to help with clearing up the bomb damage. By the time the war ended most streets around Deptford and Lewisham had buildings missing where the bombs had landed. It was amazing really that we came through it all. I’ve heard it said that the people who stayed at home suffered worse that the men who were in the army in some areas. The civilians took the brunt of it all.

Towards the end of the war my Aunt Martha moved to Adolphus Street, and there was an empty house next door and this one had 3 bedrooms. So we packed up our stuff and moved next. Although the war was coming to an end, there were still air raids and the Germans also sent over the “V” weapons, doodlebugs, mostly during the day. There were no warning sirens for those: the buzz would get louder overhead the bombs could be seen going through the air with a flame coming out of the end. The only time we were wary was when the noise stopped . Then we ducked for cover, because when the engine stopped the bomb was going to come down.