Bombs dropped in the ward of: Chaucer

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Chaucer:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 73

- Parachute Mine

- 3

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

No bombs were registered in this area

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Chaucer

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Home again in Bermondsey after the few months sojourn in Worthing, I saw my new baby sister Sheila for the first time. She'd been born on December 5, and Mum was by then just about allowed to get up.

In those days, Mothers were confined to bed for a couple of weeks after having a baby, and the Midwife would come in every day. In our case, the Midwife was an old friend of my mother.

Her name was Nurse Barnes. She lived locally, and was a familiar figure on her rounds, riding a bicycle with a case on the carrier. She wore a brown uniform with a little round hat, and had attended Mum at all of our births, so Mum must have been one of her best customers.

That Christmas passed happily for us. There were no shortages of anything and no rationing yet.

When we found that our school was re-opening after the holidays, Mum and Dad let us stay at home for good after a bit of persuasion.

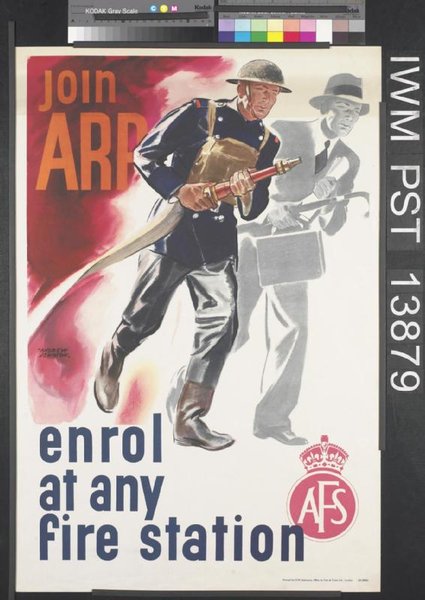

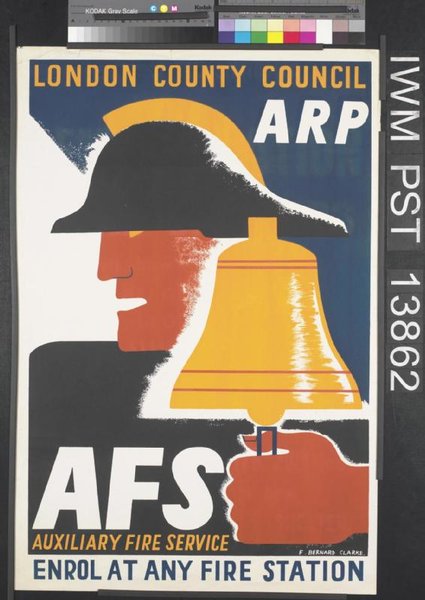

I was a bit sad at not seeing Auntie Mabel again, but there's no place like home, and it was getting to be quite an exciting time in London, what with ARP Posts and one-man shelters for the Policemen appearing in the streets. These were cone shaped metal cylinders with a door and had a ring on the top so they could easily be put in position with a crane. They were later replaced with the familiar blue Police-Boxes that are still seen in some places today.

The ends of Railway Arches were bricked over so they could be used as Air-raid Shelters, and large brick Air-raid Shelters with concrete roofs were erected in side streets.

When the bombing started, people with no shelter of their own at home would sleep in these Public Air-raid Shelters every night. Bunks were fitted, and each family claimed their own space.

There was a complete blackout, with no street lamps at night Men painted white lines everywhere, round trees, lamp-posts, kerbstones, and everything that the unwary pedestrian was likely to bump into in the dark.

It got dark early in that first winter of the war, and I always took my torch and hurried if sent on an errand, it was a bit scary in the blackout. I don't know how drivers found their way about, every vehicle had masked headlamps that only showed a small amount of light through, even horses and carts had their oil-lamps masked.

ARP Wardens went about in their Tin-hats and dark blue battledress uniforms, checking for chinks in the Blackout Curtains. They had a lovely time trying out their whistles and wooden gas warning rattles when they held an exercise, which was really deadly serious of course.

The wartime spirit of the Londoner was starting to manifest itself, and people became more friendly and helpful.It was quite an exciting time for us children, we seemed to have more things to do.

With the advent of radio and Stars like Gracie Fields, and Flanagan and Allen singing them, popular songs became all the rage.

Our Headmaster Mr White, assembled the whole school in the Hall on Friday afternoons for a singsong.

He had a screen erected on the stage, and the words were displayed on it from slides.

Miss Gow, my Class-Mistress, played the piano, while we sang such songs as "Run Rabbit Run!" "Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree," "We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line," and many others.

Of course, we had our own words to some of the songs, and that added to the fun. "The spreading Chestnut Tree" was a song with many verses, and one did actions to the words.

Most of the boys hid their faces as "All her kisses were so sweet" was sung. I used to keep my options open, depending on which girl was sitting near me. Some of the girls in my class were very kiss-able indeed.

One of the improvised verses of this song went as follows:

"Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree,

Mr Chamberlain said to me

If you want to get your Tin-Hat free,

Join the blinking A.R.P!"

We moved to our new home, a Shop with living accomodation up near the main local shopping area in January 1940.

Up to then, my Dad ran his Egg and Dairy Produce Rounds quite successfully from home, but now, with food rationing in the offing, he needed Shop Premises as the customers would have to come to him.

His rounds had covered the district, from New Cross in one direction to the Bricklayers Arms in the Old Kent Road at Southwark in the other, and it was quite surprising that some of his old Customers from far and wide registered with him, and remained loyal throughout the war, coming all the way to the Shop every week for their Rations.

Dad's Shop was in Galleywall Road, which joined Southwark Park Road at the part which was the main shopping area, lined with Shops and Stalls in the road, and known as the "Blue," after a Pub called the "Blue Anchor" on the corner of Blue Anchor Lane.

It was closer to the River Thames and Surrey Docks than Catlin Street.

The School was only a few yards from the Shop, and behind it was a huge brick building without windows.

In big white-tiled letters on the wall was the name of the firm and the words: "Bermondsey Cold Store," but this was soon covered over with black paint.

This place was a Food-Store. Luckily it was never hit by german bombs all through the war, and only ever suffered minor damage from shrapnel and a dud AA shell.

Soon after we moved in to the Shop, an Anderson Shelter was installed in the back-garden, and this was to become very important to us.

As 1940 progressed, we heard about Dunkirk and all the little Ships that had gone across the Channel to help with the evacuation, among them many of the Pleasure Boats from the Thames, led by Paddle-Steamers such as the Golden Eagle and Royal Eagle, which I believe was sunk.

These Ships used to take hundreds of day-trippers from Tower Pier to Southend and the Kent seaside resorts daily in Peace-time. I had often seen them go by on Saturday mornings when we were at Cherry-Garden Pier, just downstream from Tower Bridge. My friends and I would sometimes play down there on the little sandy beach left on the foreshore when the tide went out.

With the good news of our troops successful return from Dunkirk came the bad news that more and more of our Merchant Ships were being sunk by U-Boats, and essential goods were getting in short supply. So we were issued with Ration-Books, and food rationing started.

This didn't affect our family so much, as there were then nine of us, and big families managed quite well. It must have been hard for people living on their own though. I felt especially sorry for some of the little old ladies who lived near us, two ounces of tea and four ounces of sugar don't go very far when you're on your own.

I'm not sure when it was, but everyone was given a National Identity Number and issued with an Identity Card which had to be produced on demand to a Policeman.

When the National Health Service started after the war, my I.D. Number became my National Health Number, it was on my medical card until a few years ago when everything was computerised, and I still remember it, as I expect most people of my generation can.

Somewhere about the middle of the year, I was sent to Southwark Park School to sit for the Junior County Scholarship.

I wasn't to get the result for quite a long while however, and I was getting used to life in London in Wartime, also getting used to living in the Shop, helping Dad, and learning how to serve Customers.

We could usually tell when there was going to be an Air-Raid warning, as there were Barrage Balloons sited all over London, and they would go up well before the sirens sounded, I suppose they got word when the enemy was approaching.

Silvery-grey in colour, the Balloons were a majestic sight in the sky with their trailing cables, and engendered a feeling of reassurance in us for the protection they gave from Dive-Bombers.

The nearest one to us was sited in the enclosed front gardens of some Almshouses in Asylum Road, just off Old Kent Road.

This Balloon-Site was operated by WAAF girls. They had a covered lorry with a winch on the back, and the Balloon was moored to it.

I went round there a couple of times to have a look through the railings, and was once lucky enough to see the Girls release the moorings, and the Balloon go up very quickly with a roar from the lorry engine, as the winch was unwound.

In Southwark Park, which lay between our Home and Surrey-Docks, there was a big circular field known as the Oval after it's famous name-sake, as cricket was played there in the summer.

It was now filled with Anti-Aircraft Guns which made a deafening sound when they were all firing, and the exploding shells rained shrapnel all around, making a tinkling sound as it hit the rooftops.

The stage was being set for the Battle of Britain and the Blitz on London, although us poor innocents didn't have much of a clue as to what we were in for.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Sporadic air-raids went on all through 1943, but as Autumn came, bringing the dark evenings with it, the "Little Blitz" started, with plenty of bombs falling in our area and I got my first real experience of NFS work.

There were Air-Raids every night, though never on the scale of 1940/41.

By now, my own School, St. Olave's, had re-opened at Tower Bridge with a skeleton staff of Masters, as about a hundred boys had returned to London.

I was glad to go back to my own school, and I no longer had to cycle all the way to Lewisham every day.

Part of the School Buildings had been taken over by the NFS as a Sub-Station for 37 Fire Area, the one next to ours, so luckily none of the Firemen knew me, and I kept quiet about my evening activities in School. I didn't think the Head would be too pleased if he found out I was an NFS Messenger.

The Air-Raids usually started in the early evening, and were mostly over by midnight.

We had a few nasty incidents in the area, but most of them were just outside our patch. If we were around though, even off-duty. Sid and I would help the Rescue Men if we could, usually forming part of the chain passing baskets of rubble down from the highly skilled diggers doing the rescue, and sometimes helping to get the walking wounded out. They were always in a state of shock, and needed comforting until the Ambulances came.

One particular incident that I can never forget makes me smile to myself and then want to cry.

One night, Sid and I were riding home from the Station. It was quiet, but the Alert was still on, as the All-Clear hadn't sounded yet.

As we neared home, Searchlights criss-crossed in the sky, there was the sound of AA-Guns and Plane engines. Then came a flash and the sound of a large explosion ahead of us towards the river, followed by the sound of receding gunfire and airplane engines. It was probably a solitary plane jettisoning it's bombs and running for home.

We instinctively rode towards the cloud of smoke visible in the moonlight in front of us.

When we got to Jamaica Road, the main road running parallel with the river, we turned towards the part known as Dockhead, on a sharp bend of the main road, just off which Dockhead Fire-Station was located.

Arrived there, we must have been among the first on the scene. There was a big hole in the road cutting off the Tram-Lines, and a loud rushing noise like an Express-Train was coming from it. The Fire-Station a few hundred yards away looked deserted. All the Appliances must have been out on call.

As we approached the crater, I realised that the sound we heard was running water, and when we joined the couple of ARP Men looking down into it, I was amazed to see by the light from the Warden's Lantern, a huge broken water-main with water pouring from it and cascading down through shattered brickwork into a sewer below.

Then we heard a shout: "Help! over here!"

On the far side of the road, right on the bend away from the river, stood an RC Convent. It was a large solid building, with very small windows facing the road, and a statue of Our Lady in a niche on the wall. It didn't look as though it had suffered very much on the outside, but the other side of the road was a different story.

The blast had gone that way, and the buildings on the main road were badly damaged.

A little to the left of the crater as we faced it was Mill Street, lined with Warehouses and Spice Mills, it led down to the River. Facing us was a terrace of small cottages at a right angle to the main road, approached by a paved walk-way. These had taken the full force of the blast, and were almost demolished. This was where the call for help had come from.

We dashed over to find a Warden by the remains of the first cottage.

"Listen!" He said. After a short silence we heard a faint sob come from the debris. Luckily for the person underneath, the blast had pushed the bulk of the wreckage away from her, and she wasn't buried very deeply.

We got to work to free her, moving the debris by hand, piece by piece, as we'd learnt that was the best way. A ceiling joist and some broken floorboards lying across her upper parts had saved her life by getting wedged and supporting the debris above.

When we'd uncovered most of her, we used a large lump of timber as a lever and held the joist up while the Warden gently eased her out.

I looked down on a young woman around eighteen or so. She was wearing a check skirt that was up over her body, showing all her legs. She was covered in dust but definitely alive. Her eyes opened, and she sat up suddenly. A look of consternation crossed her face as she saw three grimy chaps in Tin-Hats looking down on her, and she hurriedly pulled her skirt down over her knees.

I was still holding the timber, and couldn't help smiling at the Girl's first instinct being modesty. I felt embarassed, but was pleased that she seemed alright, although she was obviously in shock.

At that moment we heard the noise of activity behind us as the Rescue Squad and Ambulances arrived.

A couple of Ambulance Girls came up with a Stretcher and Blankets.

They took charge of the Young Lady while we followed the Warden and Rescue Squad to the next Cottage.

The Warden seemed to know who lived in the house, and directed the Rescue Men, who quickly got to work. We mucked in and helped, but I must confess, I wish I hadn't, for there we saw our most sickening sight of the War.

I'd already seen many dead and injured people in the Blitz, and was to see more when the Doodle-Bugs and V2 Rockets started, but nothing like this.

The Rescue Men located someone buried in the wreckage of the House. We formed our chain of baskets, and the debris round them was soon cleared.

To my horror, we'd uncovered a Woman face down over a large bowl There was a tiny Baby in the muddy water, who she must have been bathing. Both of them were dead.

We all went silent. The Rescue Men were hardened to these sights, and carried on to the next job once the Ambulance Girls came, but Sid and I made our excuses and left, I felt sick at heart, and I think Sid felt the same. We hardly said a word to each other all the way home.

I suppose that the people in those houses had thought the raid was over and left their shelter, although by now many just ignored the sirens and got on with their business, fatalistically taking a chance.

The Grand Surrey Canal ran through our district to join the Thames at Surrey Docks Basin, and the NFS had commandeered the house behind a Shop on Canal Bridge, Old Kent Road, as a Sub-Station.

We had a Fire-Barge moored on the Canal outside with four Trailer-Pumps on board.

The Barge was the powered one of a pair of "Monkey Boats" that once used to ply the Canals, carrying Goods. It had a big Thornycroft Marine-Engine.

I used to do a duty there now and again, and got to know Bob, the Leading-Fireman who was in-charge, quite well. His other job was at Barclays Brewery in Southwark.

He allowed me to go there on Sunday mornings when the Crew exercised with the Barge on the Canal.

It was certainly something different from tearing along the road on a Fire-Engine.

One day, I reported there for duty, and found that the Navy had requisitioned the engine from the Barge. I thought they must have been getting desperate, but with hindsight, I expect it was needed in the preparations for D-Day.

Apparently, the orders were that the Crew would tow the Barge along the Tow-path by hand when called out, but Bob, who was ex-Navy, had an idea.

He mounted a Swivel Hose-Nozzle on the Stern of the Barge, and one on the Bow, connecting them to one of the Pumps in the Hold. When the water was turned on at either Nozzle, a powerful jet of water was directed behind the Barge, driving it forward or backward as necessary, and Bob could steer it by using the Swivel.

This worked very well, and the Crew never had to tow the Barge by hand. It must have been the first ever Jet-Propelled Fire-Boat

We had plenty to do for a time in the "Little Blitz". The Germans dropped lots of Containers loaded with Incediary Bombs. These were known as "Molotov Breadbaskets," don't ask me why!

Each one held hundreds of Incendiaries. They were supposed to open and scatter them while dropping, but they didn't always open properly, so the bombs came down in a small area, many still in the Container, and didn't go off.

A lot of them that hit the ground properly didn't go off either, as they were sabotaged by Hitler's Slave-Labourers in the Bomb Factories at risk of death or worse to themselves if caught. Some of the detonators were wedged in off-centre, or otherwise wrongly assembled.

The little white-metal bombs were filled with magnesium powder, they were cone-shaped at the top to take a push-on fin, and had a heavy steel screw-in cap at the bottom containing the detonator, These Magnesium Bombs were wicked little things and burned with a very hot flame. I often came across a circular hole in a Pavement-Stone where one had landed upright, burnt it's way right through the stone and fizzled out in the clay underneath.

To make life a bit more hazardous for the Civil Defence Workers, Jerry had started mixing explosive Anti-Personnel Incendiaries amonst the others. Designed to catch the unwary Fire-Fighter who got too close, they could kill or maim. But were easily recogniseable in their un-detonated state, as they were slightly longer and had an extra band painted yellow.

One of these "Molotov Breadbaskets" came down in the Playground of the Paragon School, off New Kent Road, one evening. It had failed to open properly and was half-full of unexploded Incendiaries.

This School was one of our Sub-Stations, so any small fires round about were quickly dealt with.

While we were up there, Sid and I were hoping to have a look inside the Container, and perhaps get a souvenir or two, but UXB's were the responsibility of the Police, and they wouldn't let us get too near for fear of explosion, so we didn't get much of a look before the Bomb-Disposal People came and took it away.

One other macabre, but slightly humorous incident is worthy of mention.

A large Bomb had fallen close by the Borough Tube Station Booking Hall when it was busy, and there were many casualties. The lifts had crashed to the bottom so the Rescue Men had a nasty job.

On the opposite corner, stood the premises of a large Engineering Company, famous for making screws, and next door, a large Warehouse.

The roof and upper floors of this building had collapsed, but the walls were still standing.

A WVS Mobile Canteen was parked nearby, and we were enjoying a cup of tea with the Rescue Men, who'd stopped for a break, when a Steel-Helmeted Special PC came hurrying up to the Squad-Leader.

"There's bodies under the rubble in there!"

He cried, his face aghast. as he pointed to the warehouse "Hasn't anyone checked it yet?"

The Rescue Man's face broke into a broad smile.

"Keep your hair on!" He said. "There's no people in there, they all went home long before the bombs dropped. There's plenty of dead meat though, what you saw in the rubble were sides of bacon, they were all hanging from hooks in the ceiling. It's a Bacon Warehouse."

The poor old Special didn't know where to put his face. Still, he may have been a stranger to the district, and it was dark and dusty in there.

The "Little Blitz petered out in the Spring of 1944, and Raids became sporadic again.

With rumours of Hitler's Secret-Weapons around, we all awaited the next and final phase of our War, which was to begin in June, a week after D-Day, with the first of them to reach London and fall on Bethnal Green. The germans called it the V1, it was a jet-propelled pilotless flying-Bomb armed with 850kg of high-explosive, nicknamed the "Doodle-Bug".

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!

Contributed originally by Thanet_Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

It was Saturday, 7th September 1940, that my first experience of war came about. A scale of indescribable terror, fear for my life and later horror and shock. All in less than 24 hours.

Nearly 17 years of age, I was then working in the Head Office of City and West End Laundry, in New Kent Road (London), the works factory was on the opposite side of the road. My manageress was a Miss Forrest, a lovely natured lady, who lived well outside London at Ashtead.

The day was beautiful, warm and sunny. Miss Forrest asked me if I would go over to one of our offices and collect the takings and Account books. The office was at Bermondsey, SE london. So, having eaten my lunch. I set off. Out of the New Kent Road, into Old Kent Road, turning off then towrads Bermondsey and eventually into Ilderton Road (I belive that was the name, at least it has always stayed in my mind), at the bottom accorss was Rotherhithe new Road, across was Rotherhithe New road, accross the way lay the Great Surrey Commercial Docks, others were around e.g. West India Docks, Victoria and Albert etc.

I found our office, alongside it were several shops with flats above, occupied by families. The air raid sirens had already sent out the warnings and the vibration of heavy aircraft around. I had just got inside the door of the office when the young women in charge of it, grabbed me quickly to take shelter, this was down in the basement.

I could dimly see the other occupants, among them a couple with a young baby. We were all sat on flattened cardboard boxes. Bombs started to fall rapidly, explosion closer. Suddenly, a huge erruption shook our basement; small concrete pieces, dirt and dust enveloped us like a cloud. Once it settled I noticed that the young mum was feeding the baby and had a hankerchief to shiled the babys face. then one of the men detected the smell of gas, but could not find the source, it was a sickening smell. Two of the mentried to move the basement door, but that was splintered and jammed tight. Their efforts only made more dust. I cannot recall anyone mentioning the time at all; perhaps it meant nothing to us then.

Later, we could hear voices and movement, mens voices. we raised ours too, over and over again, no response. Some time after it went quiet. Nobody spoke a word, amybe we were all realising there was no way out. the baby became fidgety and started to cry. Nothing seemed to console it so it went on and on.

Then we heard voices, indistinct. We shouted again and again. More movement of something, then a voice clearer than bfore, nearer and we shouted again. the came questions. 'How many were we?' 12 and a baby. 'Anyone injured?' No. our message confirmed, we were told a rescue squad was on its way. Then one of our spokesmen called out that there was a gas leak in the basement too.

It seemed an age before anything happened, but help came eventually after mroe dirt and grit showered down, we were helped out.

It was dark by this time but everything glowed fiery red, flames sky high, it was indeed a terrible sight. Shops, flats gone, contents strewn everywhere.

There was nothing, except endless pieces of conctret, lumps of broken brickwork, glass, smashed huge pieces of timber, an endless mass of debris. it was a question of stumbling, feeling our way over it all, assisted by the men who cam to our rescue.

We were told that it was the baby crying that had saved our lives. A rescue worker on his own, amking his way across, heard it and nobody else around, realised someone was trapped beneath and bought back the rescue squad.

It was about midnight by this time. We were checked out at a sort of brick shelter somewhere around. names and flat numbers were taken also my name and address. it seemed a number had been rescued but no idea as to whether all of them were found.

The companions I had shared the basement with were taken to a shelter and I never heard any more of our laundry shop girl/woman. When my turn came I said I had to get home. A warden walked with me for a while, helping me to reach the main road, the I started on my way home.

Every where was lit up by these tremendous dock blazes. Firemen could be seen high up on fire escape type ladders, using hoses, silhouetted against the red glow in the sky. air raid wardens, rescue workers carrying ladders etc even civillians helping out where they could.

I got a far as the New Cross tram depot when a policeman stopped me, wanting to know where i was going and I told him 'home to Catford'. 'Not tonight my dear' he said, and promptly escorted me into another air raid shelter. This was a brick type shelter. I realised then that another air raid had started, planes, heavy sounding, seemed very near.

Inside the shelter were several people, a lady in a wheelchair was at the far end. Bombs were falling, the usual whish and explosion. Suddenly everything seemed to erupt. i saw the wheelchair lady thrown, as i too went likewise. A split second and that was it. I remember being carried away somewhere, I know it was sheltered, someone was talking and I couldnt answer. then i was propped up and given a cup of very sweet tea, at least thats what I think it was.

More questions, where did i live? Could i stand? Could I use my arms? I thought my Head was broken. i couldnt think properly. i noticed it was daylight, and oh! How I wanted to get home. Well, in the end someone decided to allow me to go.

I just walkedand reached home at about 7.00am. This was Sunday 8th September. My mum and dad came to the door. Mums first words were 'Wherever have you been?' Dad put his arms round me and led me indoors. Gradually it came out and it was then I cried and couldnt stop. I remeber dad holding me so tight. I was safe, alive and home.

They cleaned me up. Oh! How I hurt! My head and face covered in dust and ried blood. Later the bruising came out, arms and legs. Apparantly they had seen the Dockside areas blazing from where we lived. A good viewwas had across the London area.

Monday morning my mum helped me bathe, thenshe took me to our doctor. He examined me and i was given a note for me to be off work until I felt better. he prescribed some tablets too and abottle of medicine. However, I returned to work in a few days, travelling there by clambering onto lorries mostly. Drivers were very kind and helpful. Miss Forrest was so pleased to see me back again.

The second time I was caught out, happened after I had to cycle to work.The roads were damaged, tram lines twisted and some broken etc. Cycles were sued very much in those days, war or no war. From Catford I would travel through Lewisham then on down to New Cross Road and into New Cross Gate, where I had to turn into old kent Road. At that point I suppose there may have been about 40 or 50 cyclists waiting to cross the road.

We all shot over, but once across we had not gone many yards when with a 'whoomf!' an unexploded bomb went off. I don't know what happened to the others, a couple of policemen and civillians helped wherever they could.

I had gone through a shattered brick wall to by left. once helped up and asked if I was all right, it was my bike that concerned me. I found it many yards up the road on my right, the tyres had completely vanished, blown away by the blast. And the bike, that looked as if it has been wrapped round a lampost!

I went to work. Miss Forrest cleaned me up, my head hurt and my face was grazed and so sore. She sent me home early that day.

usually when unexploded bombs were discovers roads were cordoned off and a danger sign erected. However, many could go into a soft area and be undetected, as this one obviuosly was. On my way home, I noticed workers were at the spot on the job. There was a fairly large crater made by the explosion, and very near to the wall I had gone through.

My cycle? probably used in the war effort for scrap iron!

The last of all was on a day when I was busy making up books in our office. The sirens had gone and my Miss Forrest had called me to take cover. However, there didnt seem to be much going on, so i went on with my book. Suddenly, whoosh! then an explosion, all in a split second. Our heavy glasss roof had fallen in and a piece of shrapnel stuck in the wooden bench where I stood. Later I took the piece home with me and it was kept by my mum. I never saw it again as we moved to Brockley. I had changed my job. the laundry works were damaged and our shop closed. End of that chapter!

At 17 years of age I volunteered for the Women's Land Army. In moving, my uniform had been sent to my old address. Then when i made enquiries, another appointment was made and the opportunity to go to a new branch, the Women's Timber Corps, which I jumped at a really different and unusual type of job. It was a challenge!

At the time of these happenings, the Doctor who I had seen after the first inncident, suggested I wirte about it, perhaps to rid myself of part of the horror. Counselling myself?

I wrote endless foolscap pages for there were constant occurences, not all tragic, there was a great deal of humor too. Blimey! There neede to be!

An elderly Uncle of the family who had shared our shelter, a retired gentleman, who had worked part time in publishing, on reading my account, advised me to keep it, but like many other war time 'keepsakes' it disappeared.

Contributed originally by Blue Anchor Library, Bermondsey, London (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Marion McLaren of Southwark Libraries on behalf of Fred Newman and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Southwark Family Memories of WWII

by Fred Newman

In the days before the start of World War II, under the supervision of my father who was incapacitated, my two brothers who were aged twelve and fourteen and myself aged sixteen, dug out the earth in our back yard and put in the Anderson shelter – our cousin who lived with us also helped until he was called up to join shore gun batteries near Lyme Regis. On the day Neville Chamberlain said that we were at war with Germany, Dad, with his experience of gas warfare in WWI, told us to fill our long galvanised bath with water and put by its side enough blankets to cover every window, each one of which had already been criss-crossed with transparent masking tape. The air raid siren sounded just after the Prime Minister’s broadcast and my brothers and I set to soaking the blankets and putting them up at the windows. I think that we were shaking with fright and near to tears Mum and Dad putting a brave face on things. Thankfully, it was a false alarm. A week or so later both my brothers were evacuated to Seaford – neither wanted to go – luckily they were billeted in a mansion and very well looked after. Unfortunately, the owner of the mansion fell ill and my brothers were re-housed - both had to work for their keep, the younger having to collect and chop wood for the fires and clear and clean the grates etc. and the elder had to work on paper rounds and give up the money. After a while they plucked up courage and , unbeknown to the householders, sent a message home saying “Come and fetch us home straight away or we will run away and walk home”. Mum and Dad had to make sure that their gas masks and suitcases came with them. The elder brother eventually gave up a university place to become a Paratrooper. A Green - a stick fracture made him drop out to become a Medic (still having to drop from the sky) in National Service. I worked at an engineer firm and had to join their fire watching team, and with a team mate had to take a turn at the top of the building fending off the incendiary bombs (from parts of the roof) with long handled shovels and sticks. I also joined the “Home Guard” – we had manoeuvres around the streets of Southwark, using ‘half bricks’ as substitute ‘hand grenades’. We had rifle practice at Bisley. Sad to say I was not a good shot which was confirmed when I joined the Navy as H.O. when the officer thought me so bad that I must have had a faulty rifle. Fortunately, I finally served in the Navy as a Wireless Telegraphist - some time in 1941 I think. When the Elephant and Castle was bombed, I had to go into Guy’s Hospital to have my appendicitis taken care of. The nurse who removed the clips after my operation was Haile Salassie’s daughter. When back on home guard duty our patrol went, we thought, to assist an old man who’s house had just been holed, as it turned out, by an unexploded bomb. He, thinking that we wanted to loot his house, chased us out branding a big carving knife. The cousin who was in the Gun Battery in Lyme Regis had to act as cook when the main cooking staff all went down with the ‘flu. The Commanding Officer had arranged a special dinner party in the Officers’ Mess and my cousin had to cope without assistance. The Orderly Officer decided that the pudding should be plum duff and custard. Reading the instructions which said “a pinch of salt” but knowing that many portions were required, three handfuls of salt were put in. Tasting same proved to be horrendous so a large tin of cocoa was added to mask the taste. Expecting to be placed on charge when he was summoned to the Commanding Officer’s presence, my cousin was surprised to be asked for the recipe so that it could be passed on to the C.O.’s wife! Likewise, on the way home from the Med on an ocean-going mine sweeper, Jaunty said “Sparks, you will be cook tomorrow”. “Sparks don’t cook” said I. “He does on this ship, we all take our turn except the Captain and me” says Jaunty , and “”we want stew and dumplings”. That stumped me. I could cook the meat, etc., but dumplings – I did not get the mixture right so they finished up as hard as bullets and they bounced off the bulkhead when the crew missed when throwing them at me, as we went through the Bay of Biscay.

Whilst based on the Rock of Gibraltar, a member of our watch was fighting in the final bout of the Navy Boxing Championships so the Duty Watch and those on jankers, had to be his sparring partner for one round each. I was about the third round in, absolutely scared of ‘Taffy’. After prancing about for a while, I stuck my left arm out – palm outwards – and ‘Taffy’ put his chin on it when rushing in and rocketed backwards. Recovering, he was livid. It took about six matelots to hold him down whilst I hid until he calmed down again. Duty Watch also had to ‘ditch the gash’ and that was a task because all of the dustbin residue had to be ditched into the sea. To do this we had to take turns in carrying the dustbin along the top of the concrete sewage pipe, down one ladder to avoid the square vent (the top plate of which had been torn away in a storm and not replaced) and back up a ladder further along the sewage pipe, walk along to its end out in the sea, carrying the dustbin all the time. It was a nuisance, but orders were orders. All new additions had to be made aware of the rule, but one particular bloke decided that it would be much quicker to jump down onto what looked like a concrete vent cover, which was, in fact, sun baked excrement. He went straight down only saving himself from total emersion by spreading his arms out wide. We had to draw lots to recover him – it was the short straw loser’s job to do it – what a pong! He was escorted back for ablutions leaving a trail of footprint xx!x!x, and scrubbed with hot water and gray Lysol liquid and then made to smell respectable again with lashings of scented talcum powder. That experience taught him a never to be forgotten lesson! Duty Watch also had to clean the Wren’s quarters loos, and, being the Rock of Gibraltar, all channelling was on the narrow side and was often blocked – ‘nuff said! Another part of Duty Watch duties was to climb up the wooden signal towers on the very top of the Rock and tighten up all the bolts and nuts which became loose during the heat and the levant (a moister cloud which formed by colder clouds circling the hot rock top). I could not get my body into the topmost parts of the wooden towers (did not want to, either, because from that height the ships in the bay looked like toys). So I made a swap of that part with someone who wanted a safe seat on the lorry that careered up and down the roads. Drivers were not allowed to use hooters or horns and had to bang the side of their cabs to warn of the approach. Spanish people were allowed to come onto the Rock in the morning to work and go back at curfew time! Most Gibraltarian women and children were relocated in England etc. for duration of the war. Signal reception on the Rock was, at times, hazardous – not so bad though when ‘Old Stripey’ used to rattle the sides of the Nissen huts to get us awake in the mornings before turning the bunks upside down, or when the destroyers dropped depth charges in the bay to ward off midget subs from the sunken Italian ship from the Algecira’s side of the bay.