Bombs dropped in the ward of: Holborn and Covent Garden

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Holborn and Covent Garden:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 134

- Parachute Mine

- 4

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

No bombs were registered in this area

Memories in Holborn and Covent Garden

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by Michael McEnhill (BBC WW2 People's War)

Germ Warfare.

"And some are sung and that was yesterday

And some unsung,and that may tomorrow be".

Francis Thompson (1859-1907)

"Stop there!" A harsh voice came out of the darkening night.Susan McGinley brought her bicycle to an abrupt stop at the very top of the steep Black Lion Hill, Shenley.

Preventing her from going any further and shining his torch directly into her dazzled eyes, the village policeman surveyed his "catch!" Close up, he took in the firm set face with blue rebellious eyes. Perched on her head was a navy blue cap which matched her coat,of such length it draped her knees, outlining the sheen of fine, strong legs.

He pressed her with questions. "What was she about at this time of night with a war on? Where to? Where from?"

After giving her name, she told him that she lodged at the base of the hill with her married sister, but that she was originally from Altaneerin, in Donegal, if he would know where that was. She was going to her place of work until he had stopped her. She had still three more miles to travel to Clare Hall Hospital in South Mimms. She was a qualified State-Enrolled nurse in an urgent hurry to get to her work in time, war or no war, and attend to desparately ill patients.

The policeman showed no inclination to be rid of her or to listen to her entreaties as to the plight of her patients or her own personal position. Rather, on this cold night in the latter part of January 1941, the policeman officiously pounced on the fact that her rear light was not functioning, to which Susan McGinley weakly exclaimed that she had tried reviving her battery on the kitchen range, but it must be "whacked" and that she would have to purchase a new one.That was not good enough for the policeman who summoned her to appear before the Magistrates Court at Barnet.She would have to push her bicycle the remainder of the way to the hospital where she worked.

She struggled along the lane,fearful, solitary and weary.At times a rake of searchlights sent up pillars of light into the black sky to laser back and forth.At ground level anti-aircraft emplacements were ready to puncture the night air, the banter of the crews reaching her across the leafless hedges.

The Matron,Mrs Spaley, gave her a severe talking to when she arrived late. However,it was not until a few weeks later when Susan McGinley was fined ten shillings by the Court and her case had made the columns of the Daily Express that the indignant Matron gave full vent to her feelings."I admire your fine words which have found their ways into the paper, - 'as a nurse it was my duty to relieve the sick and suffering'. However,I take grave exception to the fact that you made the location of this hospital thoroughly well known to Mr Hitler and his cronies, and I, myself, and all my staff, will be forever up and down to the air-raid shelter from this time on.I've a good mind to sack you!"

She discussed this proposal with the Medical Superintendant, Dr Simmonds, who opined that it was for her only to decide. Fortunately Dr.Laird the surgeon of the hospital came to her support declaring that she was an excellent nurse and should continue to be employed by the hospital.

Thereafter, she lost herself in her work, putting her patients before herself.'Self' in those days was a luxury one could not afford, one's patients were always at the forefront of one's thoughts. The hospital at Clare Hall had moved from Clerkenwell and was originally devoted to the treatment of small-pox diseases and has a history of over two hundred years, being situated here in 1896. The incidence of small-pox was high in 1901, and the surrounding village suffered for which the hospital was blamed for the contagiousness of disease.

At that time nurses were recruited from the old Nurses' Co-operative Society at three guineas a week, a sum regarded as a high reward, for only the best nurses were to have charge of such a serious disease.

It was in May 1911, that Clare Hall Hospital treated patients with tuberculosis. It was used for treating advanced tuberculosis patients so there was an air of gloom and despondency about the place in 1935: 39% of the patients were discharged by death; with better investigation and treatment results were more cheerful and patients were happier. Although the known causation of the disease at this time had been isolated as Koch's Bacillus, it was still maintained by medical practitioners that one could not cure a fool of tuberculosis owing to the treatment being long and troublesome.

With the diminution of small-pox cases medical forces were directed against this more prevalent scourge and it took all the resources of the medical and nursing staff, both mental and physical, to forestall its ravages of the population.

USA Army Surgeon-General Bushnell's famous remark lies at the base of all treatment: "For tuberculosis we prescribe not medicine but a mode of life".

This is where Clare Hall Hospital and its nursing staff came into their own. As the disease was highly infectious the patients had to be isolated. Endless steadfastness, courage, self-discipline and self-denial were required of them. They were housed in a hutted sanatorium which was part of the Emergency Medical Service. The 'huts' were of brick construction with asbestos sheeted roofs.At the onset of the war it was adapted as a general hospital to meet the needs of the civilian casualties, acting as a base hospital receiving local and transferred air-raid casualties from London.

However, very soon the need for a special effort to combat tubercullosis under war conditions meant that all the beds were occupied with tubercullosis patients by December 1942, a total of 540 beds.

Surgical methods of radical character only began just before the war.

Susan McGinley worked throughout the war.There were several hundred nursing staff employed at the hospital during this time.Nurse McGinley tells me that at least half the nursing staff were from Ireland, 'from the four corners, as they say'; she herself enthuses that they indeed were a credit to their country.While others were fighting a mighty battle in Europe and in the desert sands of Africa and even further afield, she and her colleagues were fighting the furious tuberculosis disease, with no let up,in the sanatorium in South Mimms.

The nursing regime was arduous for the disease requires very skilled treatment, the esentials of which are: rest, both of mind and body, fresh air and sunlight, routine and discipline, and correct feeding. By its very nature of confinement, owing to the disease being highly infectious, the disease was doubly trying and the barrier nursing required scrupulous attention to the rules of hygiene. Patients were confined to to bed at night for ten to twelve hours, necessitating more blanket baths, more bed linen changes, and all this with very difficult and demanding patients.

Along with the tremendous bouts of coughing, pain and all round debilitating ill-health, the patients exhibited what was known as a TB temperament when they would be very irritable and show extremes of temper to the nurses or for that matter anyone else who happened unfortuantely to cross their firing line.

Nurses would suffer and be expected to take many a 'tongue-lashing!'At such times the patients could also 'act-up' when smuggled cigarretes would be secretly smoked under the sheets in their beds. They would also abscond by donning a flying jacket or army greatcoat or such like over their pyjamas and make haste for the 'Old Guinea Pub' a few hundred yards from the main gate with, invariably some nurses in hot pursuit. They would be read the riot act and threatened with immediate expulsion from the hospital.No doubt within a few days they would be welcomed back into the folds of tender and loving care again.

Dr. Simmonds, in a Medical History of Clare Hall Hospital says: 'With the decline in the incidence and mortality of tuberculosis the hospital should be used for pulmonary, cardiac and other chest conditions. Tuberculosis had been largely beaten at that time and the nursing staff deserve to be honoured for relieving the suffering of many thousands of patients and making known to people not only the essential cure of the disease but also the socio-economic origins in poor housing, environment, diet and life styles".

Now, there is nothing left to tell the tale, just the sycamore tree with fresh new branches, where the nurses used to sit many years ago.

There is a worthy adendum or supplementary history to this story surrounding Susan McGinley's exploits during World War 11.

The people of America alerted by 'The Philadelphia Inquirer' as to her predicament in being dragged before the courts at Barnet were outraged that this should happen to a valuable night-nurse during the blitzkrieg, of London.

About to enter the war themselves it was a subject of contention throughout America as to the conduct of the War. They went so far as to invite Susan to their country and promised to provide her with a new bicycle.She would be paraded in the great cities as the 'Florence Nightingale Flyer' who defied Hitler during the height of the Blitz determined to see to the wounded and dying serviceman injured during the war. A medal would be cast in her honour.

Years later we were invited to contribute to Guy Michelmore and Louise Bachelor's programme retrospective film 'Memories of War' but I am sad to say nothing came of it. There was talk of the film being too expensive.

Contributed originally by quickDenis1 (BBC WW2 People's War)

The Blitz — both frightening and exciting

Denis Gardner

Not quite 14 years old when the Blitz started in 1940,

I was living at 19 Brayards Road, Peckham, South East London.

The Blitz started in earnest on the 7th of September, I think it was a Saturday and I had to get to the Nunhead railway station to pick up the evening News papers, which were thrown on to the platform from the train as it passed through the station. { The Star, Evening News and The Standard}

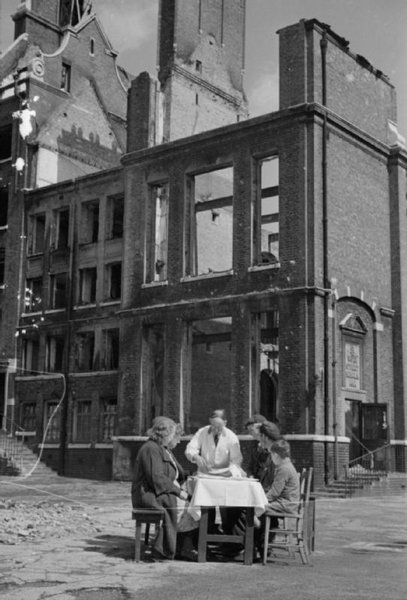

During an air raid earlier, a stick of bombs had hit this area and houses were blown down. Dust was everywhere. Gas mains in the streets were on fire. Fire engines were everywhere and hoses across the streets.

Air raid wardens tried to rescue those in the bombed-out houses, ambulances had sirens at full blast, police and air raid wardens kept people away from certain areas which were liable to collapse or had an unexploded bomb under them, and dust filled the airThe scenes of destruction, fires and mayhem were both frightening and exciting. That night they came back and bombed the East End of London, the dock area.

From Peckham we could see the huge red glow in the sky as the dockland areas with all their stockpiles of sugar, wines, rum, timber and other perishable goods burnt.

Peckham is only a few seconds flying time from the East End of London, so any pilot who was a split second off his target or was picked up by the searchlights (and lots were), just dropped their bombs to lighten the aircraft, in order to escape.

Thus thousands of homes in the surrounding suburbs were hit.

The fires in dockland burnt for days. From this day on London was bombed for 74 consecutive nights, (and sometimes during the day as well,) except for a couple of nights when the weather was too bad for air raids.

This meant going down our shelter each night and staying there, except for trips to the toilet during the quiet periods. We also had a couple who lived next door who used to come into our shelter, so there were six of us trying to sleep in this small area, and then next morning go to work, if it was still there.

One night the houses behind the house next door to us in Blackpool Street were hit. Luckily it was only a small bomb, a 250 pounder, and it demolished the top halves of both houses. When this happens the dust from the explosion is so thick it can cause death to anyone trapped.

After the explosion we always went through the drill of calling out all our neighbours’ names to see if they were all without injury. Luckily they had all survived in their Anderson shelters.

Not everyone had an Anderson shelter, some had a shelter that used the kitchen table, and made it into a sort of cage. Not very good if the house was hit, because dust then became the killer.

After any raid, everyone had their favourite story to tell. Ours was of that night. After the bomb struck we waited a while, then came out of the shelter to look around. Mum and Dad were outside and then there was another explosion.

Dad swung out his arm saying get back in the shelter and he hit Mum on the nose, which bled profusely. To stop the bleeding he gave her the towel from the outside toilet, the towel used to clean the toilet seat. I think that tale was told many times.

We lost the windows at the back of the house.

An air raid is horrific, not just from the bombs but also from the anti-aircraft guns that make a terrible noise, and the shrapnel that rains down afterwards.

Also lots of our own shells came down and exploded on contact with the ground.

Our worst fright came from the huge guns that were mounted on mobile railway platforms. The noise when these fired was terrifying: it was worse than hearing the screaming of a falling bomb.

It was said “ if” you heard the screaming of the bomb then that one was not meant for you.

These guns were supposed to help our morale, as there was not much opposition to the raiders in the early days. The railway line from Rye Lane to Nunhead ran only a few hundred yards away.

It was during one of these night raids that I got my first official cigarette. Dad and I were standing in the doorway of number 19, looking out to the street, guns were firing, search lights were probing the sky and it was nearly as bright as day time.

He rolled himself a cigarette and also one for me. I forget the exact words he said but the cigarette was to give me some form of courage from what we were witnessing. The street had just been hit by some fire-bombs.

They had all been extinguished by the people who lived in the houses. We had been lucky as they had missed our house but we all still had to be watchful. From the doorway we could see along the street, and the first sign of a glow in a window was the warning that a fire was starting.

Everyone was looking out for their neighbours. The friendship and camaraderie that exuded during the Blitz was wonderful to behold. Everyone was friendly and ready to help. Adversity brings out the best in people.

While this was happening at night we were also having some air raids during the day. This was the period when Goering had told Hitler that his Luftwaffe would bring England to her knees and she would ask for an armistice.

Though the bombing of London caused widespread damage, the bombing did not cause enough damage to commerce and industry or to the morale of the people to bring Britain nearer to surrender.

One man in England at this time thought the English were finished and that was J.F. Kennedy's father, Joseph, who was then the United States Ambassador to the Court of St.James. It was good that President Roosevelt did not agree with him, though it was still another year before America was to be drawn into the war.

As most of the thinking in America was that England was done for, their great worry was that the Royal Navy would fall into German hands.

The newspapers were telling us that the R.A.F. today shot down 144 planes for the loss of only a few of our own planes, whereas in later years we found out that the correct total had been 71 and 16 of ours lost for that particular day.

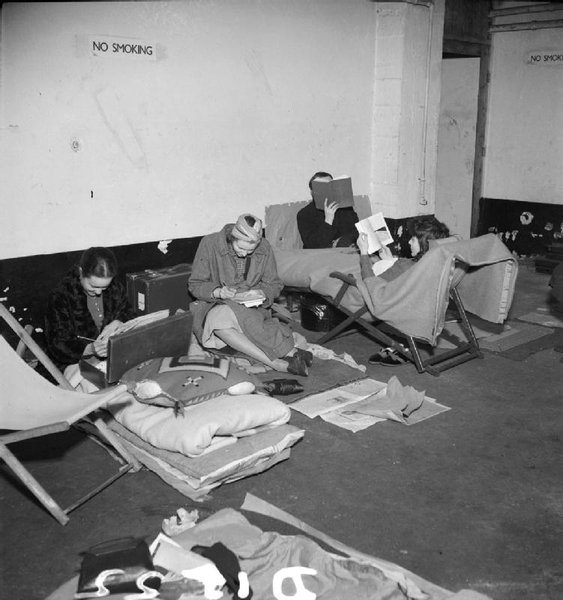

Residents of London adapted a new style of life that included sleeping every night in a damp air raid shelter underground. The cold and damp brought on a 10% increase in tuberculosis, sometimes more dangerous than the raids.

The German invasion of England was first planned for the 21st of September, but after this it was put back, and then eventually abandoned.

It was during this time that the L.D.V. (Local Defence Force) started, later renamed the Home Guard (Dads Army). They were armed with some First World War rifles, pikes and broom handles.

One of their duties in Peckham was to guard the canal, the Grand Surrey Canal. All signposts were taken down so the German troops wouldn't know where they were when they invaded.

For myself and all of my mates it was a great time of adventure. Because of the air raids lots of children, who had come back to London during the phoney war, were now being evacuated again.

Some of the kids who had rich parents were being sent to Canada. One boat that had 90 evacuees on board was the City of Benares. On the 17th September it was sunk by a German submarine during a raging gale in the Atlantic Ocean. Only a few of the children survived.

This was all happening during the months of September, October and November, 1940. At the end of September I left the paper shop at Nunhead and started another job with a paper shop nearer home.

The woman who owned this shop was a either a widow or her husband was in the forces for I never saw him. She did not have an Anderson shelter in the back garden but the hallway of the house had been reinforced to make a shelter.

She had said if a raid started during the time I was delivering papers I was to make my way back to the shop and take shelter in the hallway of her house. On the morning of the 15th October the siren sounded so I finished the deliveries in the street I was in, and then I started to make my way back to the shop.

On the way I could see German aircraft in the sky and I could see bombs leaving the planes. It was fascinating. There were other people around all staring at the sky. I carried on cycling into Caulfield Road, for the shop was at the bottom of this street where it met Lugard Road. The next thing I remember was being put in an ambulance and being taken to St.Giles Hospital. A bomb had hit a house as I was cycling past. I had cuts on the forehead and back of the head. Also my wrist was cut and my arm was in a sling.

They told me afterwards that my great concern was whether my bike was O.K. I was an outpatient at St Giles until the19th November. (I still have the certificate from the hospital).

It was most tragic at the hospital that morning, as a food factory in Camberwell had been hit and lots of young girls, the workers, had lost their lives or were severely hurt.

I did not go back to delivering papers any more. I was now the local hero, head bandaged and arm in a sling. A woman came up to me one day and said that she had pulled a kerbstone off my head.

The raids were still happening but we were getting used to them and life still had to go on. (No counselling like they give to any victim nowadays, it was called internal fortitude then.)

During all this time Mum would still have to go shopping and queue at each shop to get the meagre rations, and some times after queuing she would be told they had sold out. I think in those far off days each housewife flirted with the butcher to try and get a rabbit or some poultry that wasn't rationed.

In 1944 I volunteered for the RAF and was called up on the 15th May 1944, served in India and Burma. for two and a half years. Demobbed December 1947

Am now a member of The RAF Association of Queensland.

Denis Gardner, Brisbane, Australia, 2002

Contributed originally by joesoap33 (BBC WW2 People's War)

The Blitz — Both frightening and exciting

Denis Gardner

Not quite 14 years old when the Blitz started in 1940, I was living at 19 Brayards Road, Peckham, South East London.

The Blitz started in earnest on the 7th of September, I think it was a Saturday and I had to get to the Nunhead railway station to pick up the evening News papers, which were thrown on to the platform from the train as it passed through the station. {The Star, Evening News and The Standard}

During an air raid earlier, a stick of bombs had hit this area and houses were blown down. Dust was everywhere. Gas mains in the streets were on fire. Fire engines were everywhere and hoses across the streets.

Air raid wardens tried to rescue those in the bombed-out houses, ambulances had sirens at full blast, police and air raid wardens kept people away from certain areas which were liable to collapse or had an unexploded bomb under them, and dust filled the air. The scenes of destruction, fires and mayhem were both frightening and exciting. That night they came back and bombed the East End of London, the dock area.

From Peckham we could see the huge red glow in the sky as the dockland areas with all their stockpiles of sugar, wines, rum, timber and other perishable goods burnt.

Peckham is only a few seconds flying time from the East End of London, so any pilot who was a split second off his target or was picked up by the searchlights (and lots were), just dropped their bombs to lighten the aircraft, in order to escape.

Thus thousands of homes in the surrounding suburbs were hit.

The fires in dockland burnt for days. From this day on London was bombed for 74 consecutive nights, (and sometimes during the day as well,) except for a couple of nights when the weather was too bad for air raids.

This meant going down our shelter each night and staying there, except for trips to the toilet during the quiet periods. We also had a couple who lived next door who used to come into our shelter, so there were six of us trying to sleep in this small area, and then next morning go to work, if it was still there.

One night the houses behind the house next door to us in Blackpool Street were hit. Luckily it was only a small bomb, a 250 pounder, and it demolished the top halves of both houses. When this happens the dust from the explosion is so thick it can cause death to anyone trapped.

After the explosion we always went through the drill of calling out all our neighbours’ names to see if they were all without injury. Luckily they had all survived in their Anderson shelters.

Not everyone had an Anderson shelter, some had a shelter that used the kitchen table, and made it into a sort of cage. Not very good if the house was hit, because dust then became the killer.

After any raid, everyone had there favourite story to tell. Ours was of that night. After the bomb struck we waited a while, then came out of the shelter to look around. Mum and Dad were outside and then there was another explosion.

Dad swung out his arm saying get back in the shelter and he hit Mum on the nose, which bled profusely. To stop the bleeding he gave her the towel from the outside toilet, the towel used to clean the toilet seat. I think that tale was told many times.

We lost the windows at the back of the house.

An air raid is horrific, not just from the bombs but also from the anti-aircraft guns that make a terrible noise, and the shrapnel that rains down afterwards.

Also lots of our own shells came down and exploded on contact with the ground.

Our worst fright came from the huge guns that were mounted on mobile railway platforms. The noise when these fired was terrifying: it was worse than hearing the screaming of a falling bomb.

It was said 'if' you heard the screaming of the bomb then that one was not meant for you.

These guns were supposed to help our morale, as there was not much opposition to the raiders in the early days. The railway line from Rye Lane to Nunhead ran only a few hundred yards away.

It was during one of these night raids that I got my first official cigarette. Dad and I were standing in the doorway of number 19, looking out to the street, guns were firing, search lights were probing the sky and it was nearly as bright as day time.

He rolled himself a cigarette and also one for me. I forget the exact words he said but the cigarette was to give me some form of courage from what we were witnessing. The street had just been hit by some fire-bombs.

They had all been extinguished by the people who lived in the houses. We had been lucky as they had missed our house but we all still had to be watchful. From the doorway we could see along the street, and the first sign of a glow in a window was the warning that a fire was starting.

Everyone was looking out for their neighbours. The friendship and camaraderie that exuded during the Blitz was wonderful to behold. Everyone was friendly and ready to help. Adversity brings out the best in people.

While this was happening at night we were also having some air raids during the day. This was the period when Goering had told Hitler that his Luftwaffe would bring England to her knees and she would ask for an armistice.

Though the bombing of London caused widespread damage, the bombing did not cause enough damage to commerce and industry or to the morale of the people to bring Britain nearer to surrender.

One man in England at this time thought the English were finished and that was J.F. Kennedy's father, Joseph, who was then the United States Ambassador to the Court of St.James. It was good that President Roosevelt did not agree with him, though it was still another year before America was to be drawn into the war.

As most of the thinking in America was that England was done for, their great worry was that the Royal Navy would fall into German hands.

News headlines were telling us that the R.A.F. today shot down 144 planes for the loss of only a few of our own planes, whereas in later years we found out that the correct total had been 71 and 16 of ours lost for that particular day.

Residents of London adapted a new style of life that included sleeping every night in a damp air raid shelter underground. The cold and damp brought on a 10% increase in tuberculosis, sometimes more dangerous than the raids.

The German invasion of England was first planned for the 21st of September, but after this it was put back, and then eventually abandoned.

It was during this time that the L.D.V. (Local Defence Force) started, later renamed the Home Guard (Dads Army). They were armed with some First World War rifles, pikes and broom handles.

One of their duties in Peckham was to guard the canal, the Grand Surrey Canal. All signposts were taken down so the German troops wouldn't know where they were when they invaded.

For myself and all of my mates it was a great time of adventure. Because of the air raids lots of children, who had come back to London during the phoney war, were now being evacuated again.

Some of the kids who had rich parents were being sent to Canada. One boat that had 90 evacuees on board was the City of Benares.

On the 17th September it was sunk by a German submarine during a raging gale in the Atlantic Ocean. Only a few of the children survived.

This was all happening during the months of September, October and November, 1940.

At the end of September I left the paper shop at Nunhead and started a morning paper round with a newsagent nearer home.

The woman who owned this shop was either a widow or her husband was in the forces for I never saw him.

She did not have an Anderson shelter in the back garden but the hallway of the house had been reinforced to make a shelter.

She had said if a raid started during the time I was delivering the papers I was to make my way back to the shop and take shelter in the hallway of her house.

On the morning of the 15th October the siren sounded so I finished the deliveries in the street I was in, and then I started to make my way back to the shop.

On the way I could see German aircraft in the sky and the see bombs leaving the planes. It was fascinating. There were other people around all staring at the sky. I carried on cycling into Caulfield Road, for the shop was at the bottom of this street where it met Lugard Road.

The next thing I remember was being put in an ambulance and being taken to St.Giles Hospital,Camberwell.

A bomb had hit a house as I was cycling past. I had cuts on the forehead and back of the head. Also my wrist was cut and my arm was injured.

They told me afterwards that my greatest concern was whether my bike was O.K. I was an outpatient at St Giles until the 19th November. (I still have the certificate from the hospital).

It was most tragic at the hospital that morning, for a food factory in Camberwell had been hit and lots of young girls, the workers, had lost their lives or were severely hurt.

I did not go back to delivering papers any more. I was now the local hero, head bandaged and arm in a sling. A woman came up to me one day and said that she had pulled a kerbstone off my head.

The raids were still happening but we were getting used to them and life still had to go on. (no counselling given in those far off day it was called internal fortitude then.)

During all this time Mum would still have to go shopping and queue at each shop to get the meagre rations, and some times after queuing she would be told they had sold out. I think in those days each housewife flirted with the butcher to try and get a rabbit or some poultry that wasn't rationed.

In January 1941, just 14 years and 3 months old, I started work as an Instruement Makers Improver At H.W.Sullivans, Leo Street, just off the Old Kent Roa, working there until I volunteered for the R.A..F. in early 1944 and was called up on the 15th May1944, served in India and Burma. for two and a half years. Demobbed December 1947

I am now a member of The RAF Association of Queensland.

Denis Gardner, Brisbane, Australia, 2002

Images in Holborn and Covent Garden

See historic images relating to this area: